Lizzie Llabres, our Curator for Social History and Technology has written today’s blog, looking at how death is represented in our museum collections.

She writes:

Death and mourning is something that spans history with mourning rituals deeply embedded in to society. The way people have commemorated death in the UK has changed over the centuries, with social behaviours, ceremonies and even fashion adapting to commemorate and identify those who have died and those in mourning. Like most museums across the UK, Bradford Museums and Galleries collection contains a variety of objects that show how people have remembered and commemorated those they have lost.

Mourning Jewellery has been worn throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th century to commemorate and remind the wearer and their friends and families of people who have died. When Charles I was executed in 1649 many of his subjects wore rings and brooches with the letters CR engraved on them. Mourning jewellery could consist of deaths head jewellery (jewellery with a skull or skeleton in the design), items made from the hair of a loved one who had died, jewellery with compartments such as lockets or rings with areas to store hair or an item belonging to the deceased and, by the end of the Georgian period, Jet jewellery had become particularly popular as a piece of mourning wear.

BMG has an interesting collection of mourning Jewellery dating from the early 18th century up to the early 20th century, with many pieces from the Victorian period. Jet jewellery was particularly popular in the district, possibly due to its close proximity to Whitby, which is famed for its high quality jet.

Death masks were also created as mementos of the dead. Made from plaster or wax, a cast is taken from the corpse shortly after death. In some cultures death masks were created as funeral masks and buried with the corpse. In Europe the masks could be put on display, next to the coffin, as an effigy of the deceased. Casts of peoples hands were also taken as a memento mori. BMG holds one of Oliver Cromwell’s death masks, which is currently on display at Bolling Hall Museum. The mask was donated to Bradford Museums in 1933 and is part of the Civil War display, which tells the story of Bradford as a Parliamentarian town and the Siege of Bradford by the Royalist army.

Memorials are also a way that people have commemorated and celebrated those who have died, particularly those who have died in tragic events. Bradford Museums and Galleries hold a large and varied collection of War Memorials commemorating those that died during the 1st and 2nd World Wars, as well as memorials commemorating mill disasters in the district. Many company memorials, commemorating workers from different factories across the district, can be seen on display at Bradford Industrial Museum. The Industrial Museum clock tower is a memorial to those who worked at the spinning mill and gave their lives during WW1. Stained glass on display at Cliffe Castle Museum was once part of a stained glass window war memorial in Temple Street Methodist Chapel, Keighley. War memorials are created not only as an official record of those who died during service in designated times of war, but as an object to commemorate war, conflict, victory and peace. They also act as a physical marker that people can gather at to remember and actively commemorate and hold public services to those who have died, both named and unknown, in conflict.

As well as items commemorating those who have died, Bradford also holds a collection of items that tell the story of the ‘craft’ and workers behind death and ceremony. BMG has a selection of undertakers tools, used to make coffins in the early Victorian period. One of the most interesting of these items is an undertaker’s screw driver. I know a screw driver may not seem that interesting, but it highlights the variety of tasks and activities a seemingly mundane object can be involved in. This screwdriver is recorded as being used to screw down the lids of coffins in Haworth and may have been used in some of the Bronte burials.

Early undertakers were often joiners and carpenters who also make coffins at times of death. The undertaker would be summoned shortly after death, to take measurements for the coffin. The coffin would be made from hardwood and sealed with wax and bitumen to prevent leaks. The coffin would be delivered to the family of the deceased and the deceased would be laid to rest in a room of the house until the funeral. Chapels of rest didn’t become established in funeral homes until the 1950s.

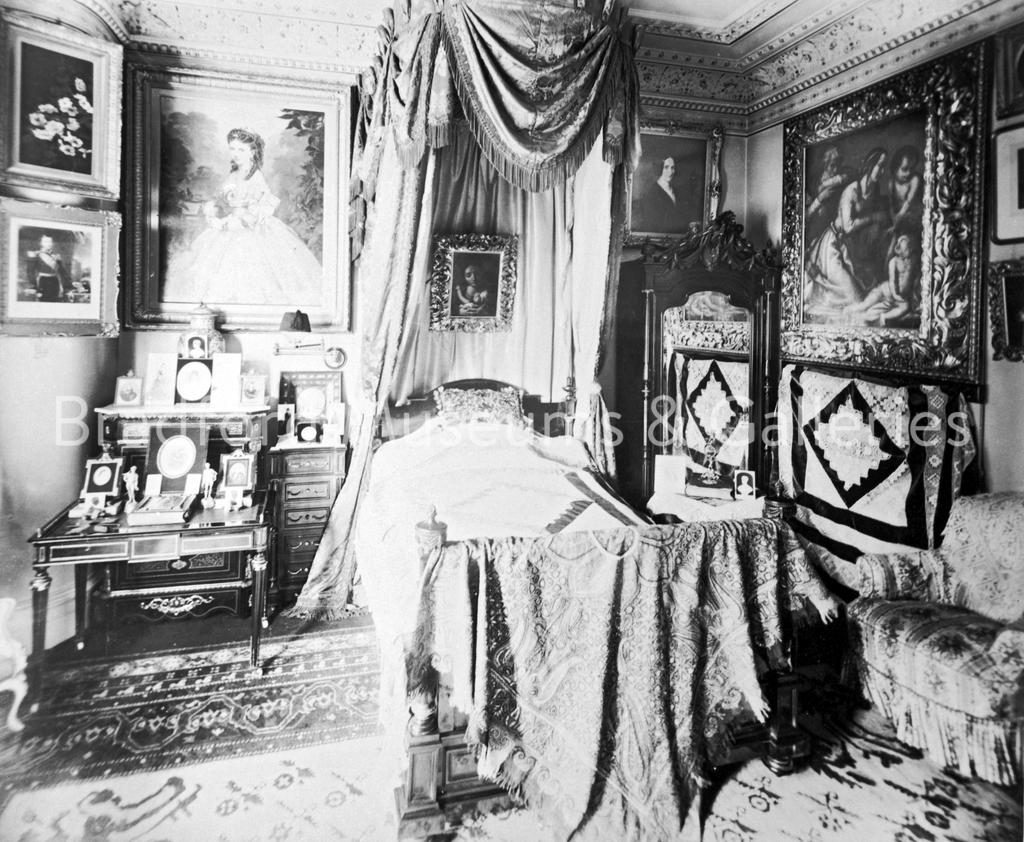

Many people also collected items to commemorate the deaths of celebrities of the day. Henry Butterfield was a devoted lover of music and purchased the death bed of the composer Rossini and had it installed in his bedroom at Cliffe Castle. Unfortunately BMG does not have the bed in its collection, as it was sold in the 1950s sale of contents by the family. We are keen to find out what may have happened to it. (If you know, please contact us).

BMG also holds an image in the collection of Bram Stoker exiting the Theatre Royal in Bradford in October 1905. As well as being the famed author of Dracula, Bram Stoker was also the manager of the acclaimed actor, Henry Irving. On news of Henry Irving’s death, at the Midlands hotel in Bradford on the 13th of October 1905, Stoker rushed to Bradford and can be seen in this image exiting the theatre after disbanding Henry Irving’s company. This image is an important part of our collections relating to death and mourning, as it’s a snap shot of a historically significant moment in time, relating to two well known ‘celebrities’ of their day.

By the time Queen Victoria came to the thrown in 1836 she had inherited an established code of mourning. When the Duke of York died in 1827, the Earl Marshal issued the following order…

‘…upon the present melancholy occasion of the death of the late Royal Highness Frederick Duke of York and Albany…it is expected that all persons do put themselves in to deep mourning.’

Fashion magazines of the time printed illustrations of suitable mourning costume, with dresses of black silk, twill worsted or cotton, accompanied by suitable and fashionable mourning jewellery.

By Prince Albert’s death in 1861 mourning had become a large and expensive affair, with degrees of mourning costume, style and colour, reducing social meetings and engagements, as well as the expense of the funeral itself. A carriage hearse and horses, memorial cards, elaborate coffins and funeral food, such as funeral biscuits are all seen as an essential part of the mourning process.

BMG holds a variety of examples of mourning costume showing the different stages of mourning dress in Victorian England. The rules of what you wore and for how long were complicated; they were outlined in popular journals and household manuals of the time to help guide the grieving Victorian in appropriate dress and etiquette. Those in deepest mourning wore black clothing made from simple, non reflective, fabrics trimmed with crape. No velvet, satin, lace or embroidery could be used. After a suitable period of time the crape could be removed and the cloth colour could be gradually lightened to grey, mauve and white. Men wore black suits along with black gloves, hatbands and cravats.

The length of time you were in mourning depended on your relationship with the deceased. Widows were expected to wear mourning costume for up to 2 years. For children the mourning period was up to 1 year. Children did not often wear mourning clothes, although girls could wear white. Grandparents and siblings were expected to mourn for 6 months. There was some flexibility in the mourning period and becoming engaged during this time wasn’t entirely disapproved of. If a widow became engaged whilst in mourning she would be permitted to discard her mourning attire.

Queen Victoria famously wore mourning for the rest of her life

Mourning rituals were slightly different for the working classes. The death rate was much higher in working class households and many families would save to ensure they had funds to cover funeral expenses, often going without necessities to ensure a proper burial for their loved ones. If they could not pay for a funeral the family would be reliant on the local Poor Union, who would provide a basic Pauper’s Funeral and they would be buried in a pauper’s grave. If they could afford to, working class households would dye existing clothing black or where black or purple arm bands to signify mourning.

Spiritualism also became popular in the Victorian period. Many people tried to communicate with loved ones who had died; joining spiritualist churches in the hope of remaining connected to and receiving a message from them. The Spiritualist movement found its UK base in Keighley in 1853; from there Spiritualism spread across the UK. Prominent members of the spiritualist movement included Arthur Conan Doyle and Lord Dowding. Unfortunately BMG’s collection relating to the Spiritualist movement in Keighley is limited and it is difficult for BMG to tell the history of the movement in full.

One Response

Fascinating post, Lizzie, enjoyed it. Going further back in time, I find the Stanbury burial exhibit in Cliffe Castle particularly moving, but also worrying. A couple of years ago I spent quite a long time drawing the pottery vessels and also the cremated bones…. wondering all the time about the ethics of removing buried remains from their resting place and subsequently putting them on display. Is it thought to be alright as long as they’re more than a certain age? When does archeology end and grave robbing begin? What’s the curatorial protocol?

Deborah