Heather Millard, Community Curator has written this latest blog about one of her favourite objects. She writes:

One of the things that makes working in museums and galleries fun is tracking down the stories associated with objects – and then getting to share them with everyone else.

If you’ve visited Cliffe Castle in the last 4-5 years, you will probably have noticed the rather lovely painting in the Bracewell Smith Hall, of a lady in a pink dress, sat by the side of a stream. It’s one of my favourite pieces in the collections of Bradford Museums and Galleries, and I’ve been meaning to write up the story behind it for some time.

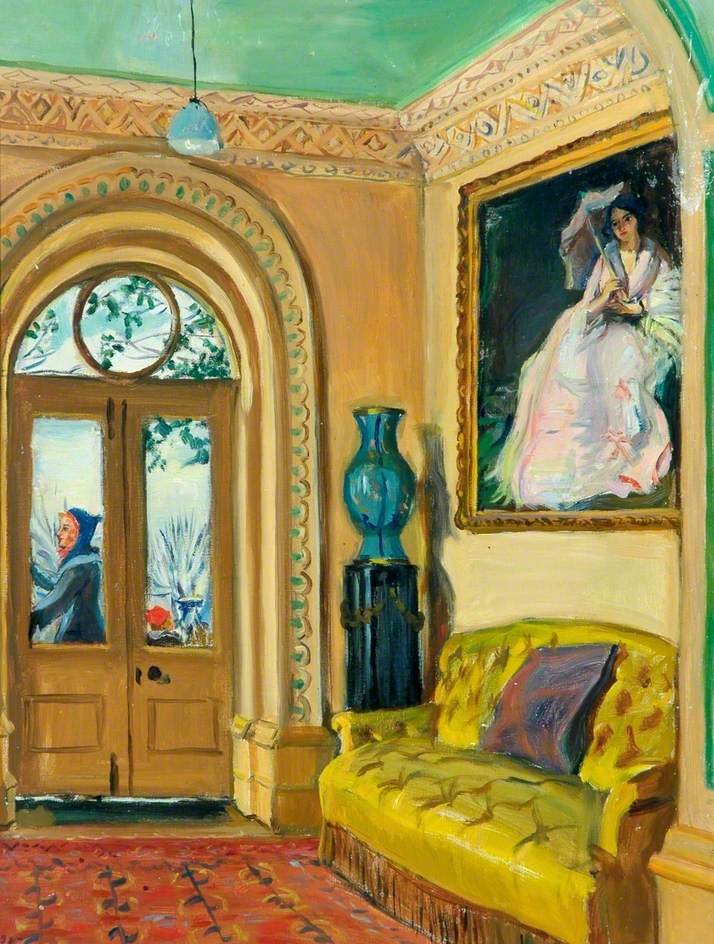

The painting was originally purchased by Henry Isaac Butterfield, as part of the collection of paintings, sculpture, furniture and decorative arts he acquired to furnish Cliffe Castle when he rebuilt it in the 1880s. We know where it was originally displayed (a part of the building that no longer exists!), thanks to a painting by his Granddaughter, Marie-Louise Pierrepont (Countess Manvers) – which shows it near the Winter Gardens.

When the Castle was sold by Countess Manvers in the 1950s, she moved a number of items including this painting, to Thoresby Hall in Nottinghamshire.

It returned to Cliffe Castle in 2016 after the death of Lady Rozelle Raynes, who was the daughter of Countess Manvers. It was part of a bequest she made to the museum of items with a Butterfield or Cliffe Castle link and a Yorkshire connection. We’ve talked about the return of the Malachite fireplace and other items in earlier blogs.

The family story suggested the ‘lady in the pink dress’ was a mistress of Victor Hugo, the famous French Author, which was rather intriguing. Such a story would certainly have fitted with Henry Isaac Butterfield’s tendency to collect objects associated with interesting people.

My colleague Daru and I started investigating. It involved identifying the subject, the artist, and it turned out to be quite the world-wide adventure to do so… (sadly, no actual travelling involved).

We identified that the sitter was a famous Mezzo-Soprano opera singer of the period called Pauline Viardot. The more we found out about her, the more intrigued we were – she was a sister to the equally famous Maria Malabran (who died at the age of 28, after collapsing on stage.) Pauline was a pupil of Franz Listz, a friend of the novelist George Sand – and as a result of that friendship, became friends with Frederick Chopin. She was also highly regarded by the composers Gounoud and Berlioz.

She was a talented composer in her own right – the video we’ve shared below is accompanied by one of her compositions – and includes some additional images of Pauline.

We’ve also created a spotify playlist with some of her compositions here if you want to listen to more of her work.

Interestingly, she was linked (perhaps romantically) to the Russian Novelist Ivan Turganev, who shared a house with her and her husband, but we could find no direct link to Victor Hugo. They were both well known in society at the time, and had some acquaintances in common, but beyond that, nothing connected them.

However, a claim that Victor Hugo had slashed this portrait in a jealous rage was clearly associated with the painting – so what led to this story?

Our next task was to identify the artist and normally, this would be fairly straightforward. Unfortunately ,the painting had been cut down from its original size (sadly, not uncommon), and the majority of the artist’s signature was lost as a result.

All we had left was a barely legible ‘…ard’ in the bottom left corner. We were peering over artists signatures from the period (with a lot of ‘does this look like it matches?’ conversations in between). Eventually we concluded it was perhaps François-Auguste Biard – a French artist, best known for his landscapes rather than portraits – and the style seemed to match.

To confirm our deductions, we searched for Dr Alvin, a specialist on the artist (he wrote Le Monde Comme Spectacle: l’ouevre du peinture Francois- Auguste Biard) to see if he agreed. This was easier said than done- as Dr Alvin lives in Brazil and we had no direct contact details. We tracked down his University on twitter, and asked very nicely if we could be put in contact!

Luckily they did so, and after a email conversation with Dr Alvin, it was confirmed the painting was by Biard.

Identifying the artist meant we were able to make the connections back to the story about Victor Hugo. Pauline Viardot, (the subject of the painting) was not his mistress, but Léonie d’Aunet, Biard’s wife, was Hugo’s lover for several years.

In 1845, Victor and Leonie were caught together in a hotel, and both were arrested. Victor Hugo’s status as a member of the ‘Chamber of Peers’ (the French equivalent to the House of Lords), meant he was quickly released with no charges brought against him. In contrast, Leonie served two months in the Prison Saint-Lazare, and was subsequently sent to a convent, where she remained for about 6 months. They later resumed their affair, until Hugo’s exile from France in 1851. Biard annulled the marriage to Leonie in 1855.

It would appear then, that the damage done to the painting was indeed by Victor Hugo, and was related to a mistress – but not the woman in the painting.

This idea of an object with a story appealed to Henry Isaac Butterfield, just like it appeals to us – so it’s not surprising he chose to acquire it. Finding out the real story behind the ‘family tales’ was a entertaining and illuminating detective story, with rather more global links than we’d expected at the beginning – so we’re glad to be able to share it with you!

9 Responses

Listening to Radio 3 Composer of the week – Pauline Viardot.

I love this picture you have.

So do we. – and the Composer of the Week programme on her is fascinating!

What a wonderful article. Thank you so much for all your detailed research. It’s a fascinating story and just goes to show that Keighley has much to be proud of and valued in its cultural collections, many of which are of national and international significance. It’s great that we also have brilliant staff and volunteers in museums who really value them and take great effort to highlight and promote them to us, the public. Thank you.

You’re very welcome! I very much enjoyed telling the story. – Heather

I brought my small grandsons to Cliffe yesterday and we enjoyed the variety of exhibits. I regret not making a donation as we left. Is there a way I can do so online?

I’m very glad to hear you enjoyed your visit to Cliffe Castle – apologies for the delay in response, we have a over enthusatic spam filter and your comment was caught in it!

You can make a donation here, https://ip.e-paycapita.com/AIP/itemSelectionPage.do?link=showItemSelectionPage&siteId=310&languageCode=EN&source=AIP then selecting ‘Museum and Galleries’, then ‘Cliffe Castle’ – and then ‘donate’. (It’s a long winded way of doing it I’m afraid, but we have to work with it!)

Or, just pop something in the donation box next time you visit – either way we definitely appreciate your support!

Such a fascinating story. Have not seen the painting but find it enthralling and perhaps the loveliest painting I have seen. Determined to come back to Cliffe Castle in near future. Thank you so much for wonderful story and all your hard work in sharing it with us. Very best regards Jo Nuttall

Very glad to hear you enjoyed the story – it was as enjoyable to write about! It’s one of my favourite paintings too.

– Heather

When was this made?