In this blog Dr Rebecca Wade, Collections Assistant (Cultural Recovery Fund), rediscovers the identities of an intriguing set of plaster casts in our collection taken from some of the most famous sculptures in the history of Western art.

“Oh we’ve got some of those,” is perhaps the most exciting sentence you can hear when you work with collections, closely followed by: “we can go and have a look at them if you like?” Those were the words of Dale Keeton (Conservation Officer) as he set about revealing the stores of Bradford Museums and Galleries as part of my induction. We were talking about reproductions of sculptures: copies in plaster, electrotypes and fictile ivories of the sort that were often acquired by early museums, galleries and schools of art as ‘object lessons’. It was thought that these copies could communicate the same lessons as the original works about form and taste, even though the context and material were different. The intention behind the circulation of these reproductions was to educate students and the wider public, with the underlying economic aim for makers to be informed by the highest artistic principles and consumers to be compelled to purchase a better class of fancy goods.

Although copies have a long history of use in art education, these ideas were especially widespread in Britain in the second half of the nineteenth century and into the first decade of the twentieth. The schools of art that were established during this time were issued with a standardised collection of plaster casts for students to draw from as part of a centralised programme of study—in effect, the very first national curriculum. At the same time regional towns and cities were encouraged to set up their own public museums and galleries to provide ‘rational recreation’ for their working populations. Reproductions represented a way to fill these new spaces with ‘improving’ works of art before they had built their own distinct collections of painting, sculpture and decorative arts.

This was certainly the case for Bradford, whose Public Art Museum on Darley Street had been founded in 1879—the ancestor of Bradford Museums and Galleries as it exists today. Schools of art had opened at the Mechanics’ Institute on Bridge Street in 1868; the Church Institute on North Parade in 1873; the Grammar School on Manor Row in 1874 and the Technical College on Great Horton Road in 1883. All had plaster casts and other reproductions as part of their teaching collections. But what happened to them?

Copies fell out of favour for two main reasons: practical and philosophical. Plaster of Paris is a porous and fragile material, vulnerable to losses and without proper care, a tendency to discolour through the accumulation of dust and dirt. Over time and with active use, the condition of these objects often deteriorated beyond the point where it was considered economical to restore them. Attitudes to reproductions had changed too: where they were once considered prestigious objects, by the middle of the twentieth century they represented a dated and limited approach to teaching art and design. As a result of these combined factors, plaster cast collections were often destroyed, disposed of, or relegated to deep storage. There are of course notable exceptions: the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Museum of Classical Archaeology and the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology for instance. There are still plaster casts to be found at some schools of art too: the Royal Academy of Arts, Glasgow School of Art, Edinburgh College of Art and Birmingham City University for example.

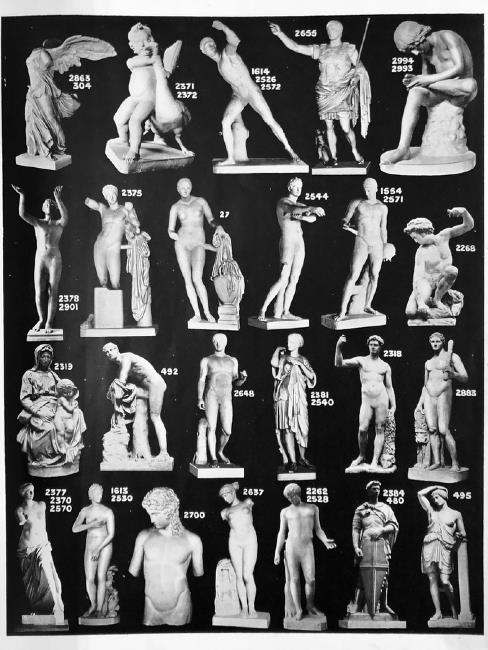

The decline in the status of these objects accounts to some extent for gaps in knowledge about them; they were not thought valuable or unique enough to document to the same level of detail as original works of art. In more recent years, however, we have witnessed increasing interest in casts and copies, which are now seen as legitimate historical objects in their own right. Once interpreted as if they were the original work, we now know so much more about the people who made them, the conditions of their production and how best to conserve them for the future. My own research has focussed on the formatore (plaster cast maker) Domenico Brucciani. Born near the Tuscan province of Lucca, Brucciani became the most important and prolific maker of plaster casts in nineteenth-century Britain. He and his business used public exhibitions, emerging museum culture and the nationalisation of art education to monopolise the market for reproductions of classical and contemporary sculpture.

Imagine my excitement then, to encounter rare survivals by Brucciani and other Italian formatori in the collection of Bradford Museums and Galleries. First we met a figure of St George, originally carved in marble by the Italian Renaissance artist Donatello in 1415-17. Now in the collection of the Museo nazionale del Bargello in Florence, Brucciani cast the statue in plaster in two different sizes: at full size for £7 and a reduced scale version at two feet, seven inches for £1 5s. It has been suggested that this particular cast was transferred from Keighley School of Art and Crafts (a precursor to Keighley College), which had been established in 1869-70.

Plaster cast collections were dominated by reproductions of sculptures from classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. We identified two further works from this latter period in the collection, both of which are circular reliefs in ebonised wooden frames intended to be wall-mounted. They both represent the same religious subject: the Madonna and Child. The first was straightforward to identify: the ‘Pitti Tondo’ by Michelangelo, carved in marble between 1503 and 1504. Also in the collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, it is likely that the cast maker in this instance was either Brucciani or his contemporary Oronzio Lelli, the official formatore of the Royal Galleries in Florence. The second relief was more challenging to identify. Although it resembled similar works by Luca della Robbia, Dr Rachel Boyd (Ashmolean Getty Paper Project Research Fellow) correctly recognised it as a copy after the early Renaissance Italian sculptor Benedetto da Maiano, the original of which is is displayed in the Cappella di San Bartolo in the church of Sant’Agostino in San Gimignano. Lelli cast a version purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1890, so it is possible that the Bradford cast is from the same source.

The final two plaster casts we encountered on our visit to the stores replicated objects far beyond the Italian Renaissance in both geography and chronology: a Pictish cross known as the ‘Nigg Stone’ carved circa 750-800 and part of a mantlepiece designed by Alfred Stevens and completed by James Gamble in 1873. The Nigg Stone was offered for sale by Brucciani for £18 18s. and at seven and a half feet tall, it was both one of the most expensive and largest plater casts in the catalogue. The additional expense is likely to have been the result of the challenges posed by the size and shape of the mould and that it was double sided. Most reliefs sold by the Brucciani company had only one side, meaning the reverse could be roughly finished and unseen against a wall. Looking behind such casts often reveals traces of the hand of the maker as the shapes their fingers made in the wet plaster set solid. The original early medieval cross is located in the parish church of Nigg in Easter Ross in the Highlands of Scotland.

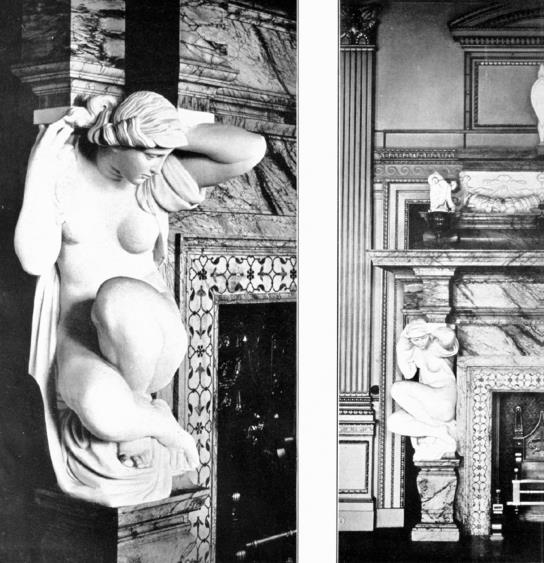

Lastly, we come to the most recent of this type of plaster cast in the collection. Commissioned for Dorchester House on Park Lane in London, the British sculptor Alfred Stevens designed and partially completed a sculptural chimneypiece for the dining room in 1869, which was saved when the house was demolished in 1929 to make way for the Dorchester Hotel. The chimneypiece was acquired by the Tate Gallery and transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1975, where it now forms part of the decoration of the V&A Café. While it was still in the Tate collection, the formatore Enrico Cantoni was engaged to cast the two female figures that supported the mantlepiece in order for the whole piece to the reproduced in plaster and wood. Presented to the Tate collection by the Alfred Stevens Memorial Committee in 1911, the catalogue entry for the reproduction read as follows:

The figures and decorative work, carried out in the original in white Carrara marble, are reproduced in plaster. The casts were taken from the original by Mr. Enrico Cantoni. The remaining parts, carried out in greenish Bardiglio marble in the original are reproduced in wood. The measurements were copied exactly from the original by Mr. Campenhoudt. The figures are slightly larger than life-size. They hold the entablature on their shoulders, their heads being thus left free. By this variation on the usual caryatid form, Stevens avoided the somewhat unpleasant effect of weight resting on the head and achieved greater freedom and dignity in the figures.

A version of this same reproduction was purchased for Bradford from the Alfred Stevens Memorial Committee two years later in 1913 at the substantial cost of £105. The price, alongside the record noting the materials it was made from were both plaster and wood, suggests that the whole chimneypiece was acquired for Cartwright Hall. As yet, only one of the plaster caryatid figures has been located, leading to the intriguing possibility that more of the piece is yet to be found.

Plaster casts and other forms of reproductions can tell us so much about the values and priorities of the people who commissioned, made and displayed them. They record the original object at a fixed point in its history, sometimes providing crucial clues to the past condition of works of art and architecture. Occasionally they become the only material evidence for objects that no longer exist. That these objects have survived in the collection of Bradford Museums and Galleries makes them rare and important. They brought early medieval Scotland, the Italian Renaissance and the finest late Victorian sculpture to Bradford. By documenting them more completely, it is to be hoped that they will one day be shown in public again.