“I adjure you elves, elvish spirits, fairies and divells”:

In this first blog of the month, ready for Friday the 13th, one of our Assistant Curators of Collections, Dr Lauren Padgett, shines a light on one of the most superstitious objects in our collection, the Lambert spell book… but all is not what it seems!

When I joined Bradford District Museums and Galleries, colleagues would talk about their favourite collection objects, ones with particularly interesting stories attached to them and ones to be wary of. They would talk of a cursed book, known as the ‘Lambert spell book’. Found hidden in one of our museums’ basement rooms with no knowledge or documentation about how it got there, it contains spells against witchcraft with curious symbols throughout. Strange events have happened to those who dared to touch it. One previous curator put warnings on its collection database record and its physical storage box. The spell book was lent to the Ashmolean in 2018 for their Spellbound: Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft exhibition but Bradford District Museums and Galleries have never displayed it, heeding the warnings. In 2025, a couple of researchers requested to see the spell book. I decided it was time to examine it myself to either confirm the superstition around it or debunk it

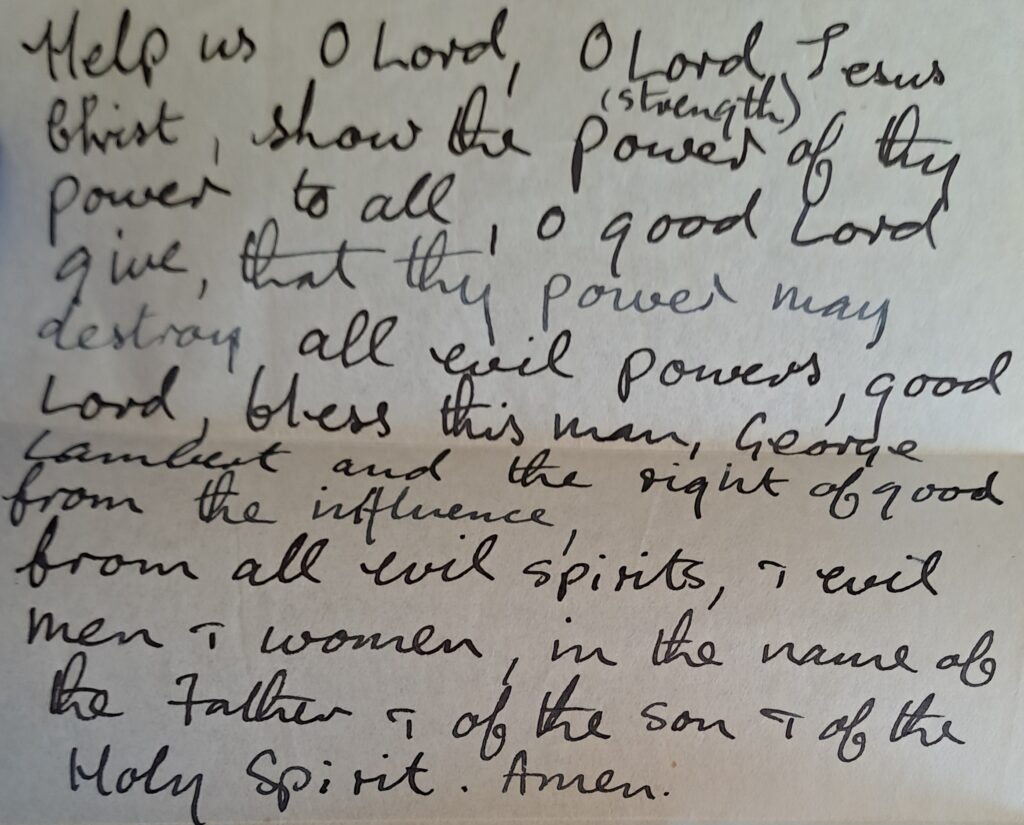

When the book (museum accession number H.2017.147.1) was initially discovered, within it was a loose piece of paper with a handwritten prayer on it (museum accession number H.2017.147.2) of a more recent date and in a different hand to the book. It says:

Help us O Lord, O Lord Jesus Christ, show the power (strength) of thy power to al , o good Lord give, that thy power may destroy all evil powers, good Lord, bless this man, George Lambert and the right of good from the influence, from all evil spirits, & evil men & women, in the name of the Father & of the Son & of the Holy spirit. Amen.

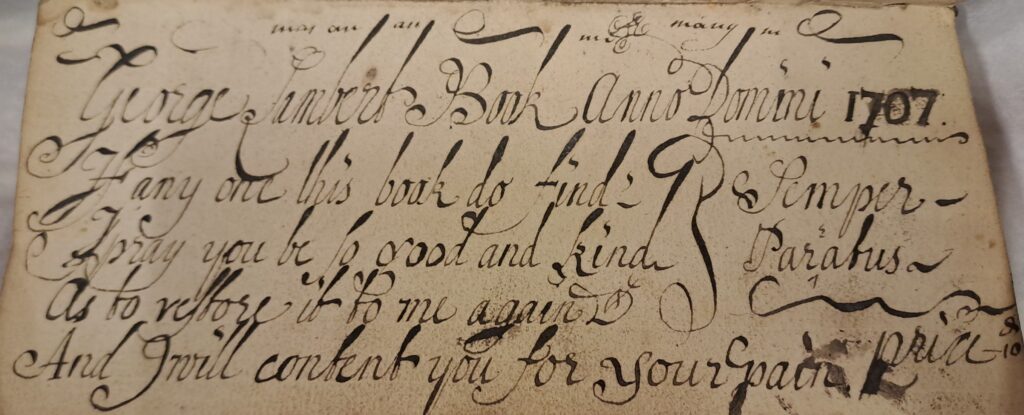

Opening the book and examining the flyleaf, it says:

George Lambert Book annon domini 1707. For any one this book do find I pray you be so good and kind as to restore it to me again and I will content you for your pains. Semper Paratus.

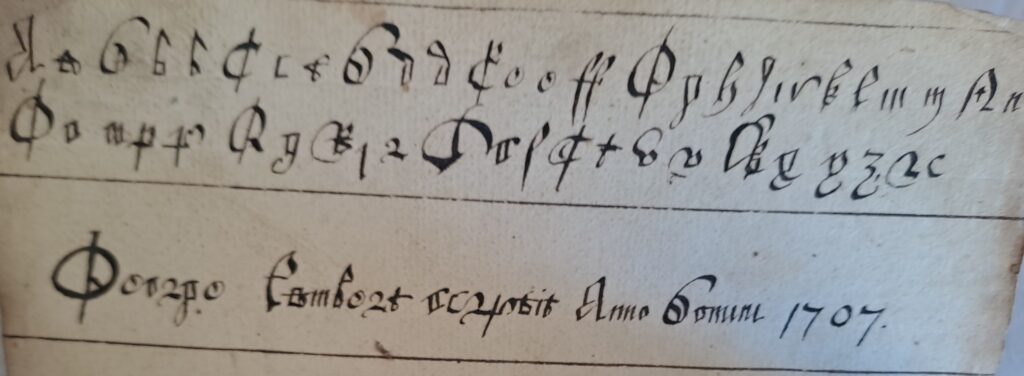

The last phrase is Latin for ‘Always prepared’. At the back of the book is text that looks almost like a handwriting exercise where, in Secretary Hand (a style of handwriting from the 1500s to the 1700s), the letters of the alphabet are written in upper and lower case, along with the name “George Lambert” and the year “1707”.

Flicking through George Lambert’s book, it is written in both English and Latin with some archaic English spellings. I have used square brackets to translate or fill in missing letters or words. Original spellings have been kept if similar to modern spelling and still understandable. While most of the book looks like it was written by one person (assumed to be Lambert) due to the consistent handwriting, other hands are present. Less formal handwriting styles of that time period such as Italic Hand and Round Hand are also used. The content of the pages includes recipes (also known as receipts), prayers, poems, financial accounts and nativities (natal/birth charts or horoscope illustrations based on the sky at the time of birth). This range of writings would suggest that the book is a commonplace book. These were personal organisers, used to record and document a compilation of information such as accounts, prayers and recipes. As the name suggests, they were an ordinary possession from the 1600s and into the 1800s; some were passed down the descendants of the family.

Let’s explore some of the contents of Lambert’s book in detail and start with the recipes/receipts as I’m in familiar territory here. In 2023, I examined a 18th-century recipe book in Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection that belonged to Ann Rookes. You can read a blog about Ann Rookes’ recipe book here.

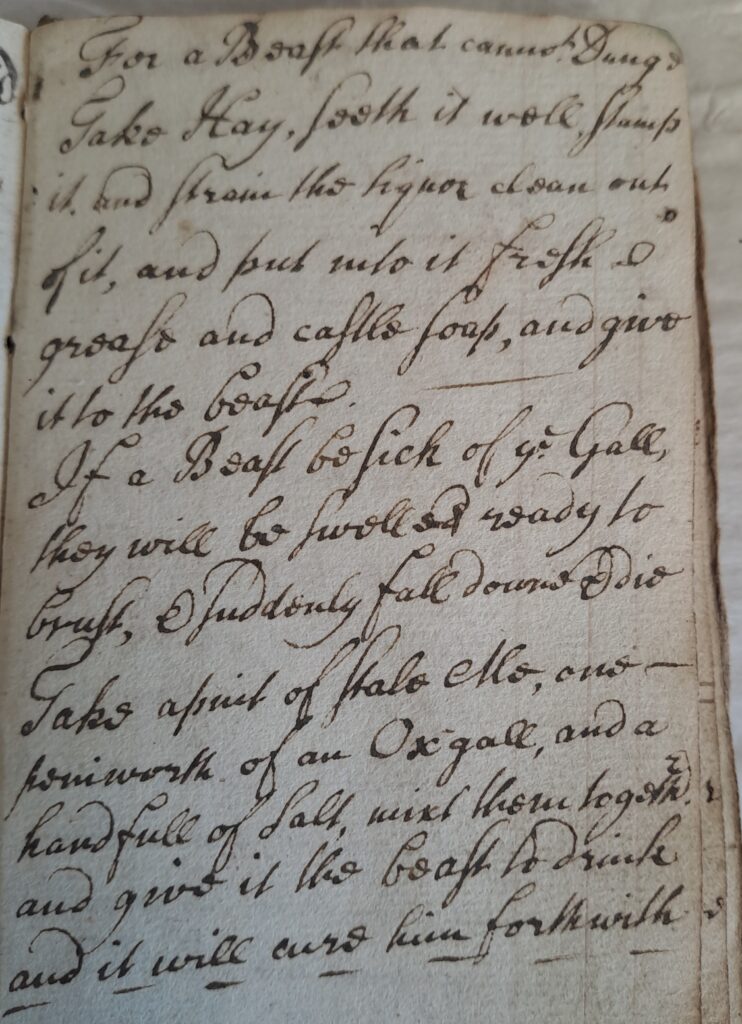

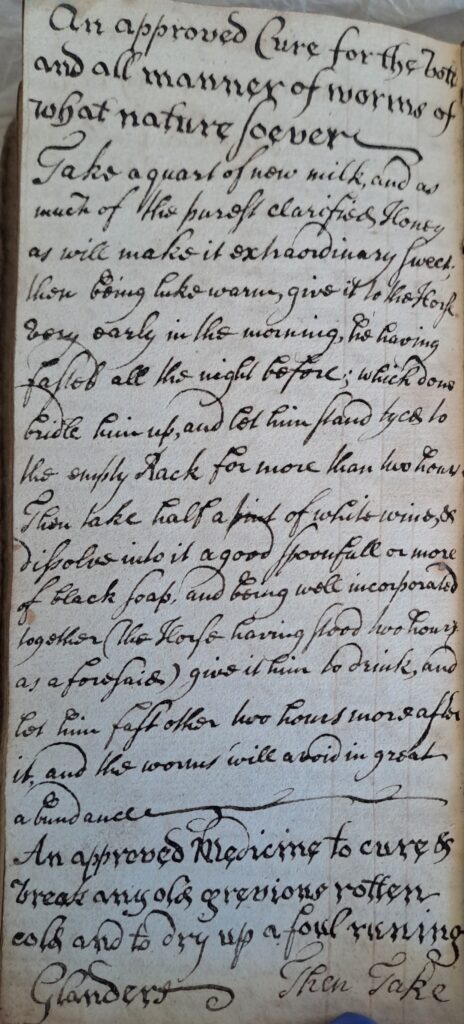

Lambert’s book has several animal husbandry remedies for ill animals. For example, “For a beast that cannot dung” a liquor of strained soaked hay and “castle [Castile] soap” “will cure him forthwith”. There is also a remedy “to make hoofes grow quickly and to be tough and stronge” and the “best receipt [that] can be for brittle hoofes”. Not just for animals, Lambert also recorded remedies for human ailments – although it is unclear at times if some of the remedies are for animals or people. For example, “for rhumatic” disorders, a long list of ingredients are itemised such as “spirit of wine”, “tincture of myrh” and “oil of spike” (which is lavender oil) with the instruction for “one pennyworth of each” and to “rub the parts affected”. This recipe is repeated with the name “Hannah Whitham” beneath it. As with Ann Rookes’ recipe book, often the name of the recipe contributor or recommender is written down with it. There is a recipe for “the true manner of making those balls which cure any violent cold or glanders which prevents heavy sickness…” as well as “an approved medicine to cure or break any old grievous rotten cold and to dry up a foul running glanders”.

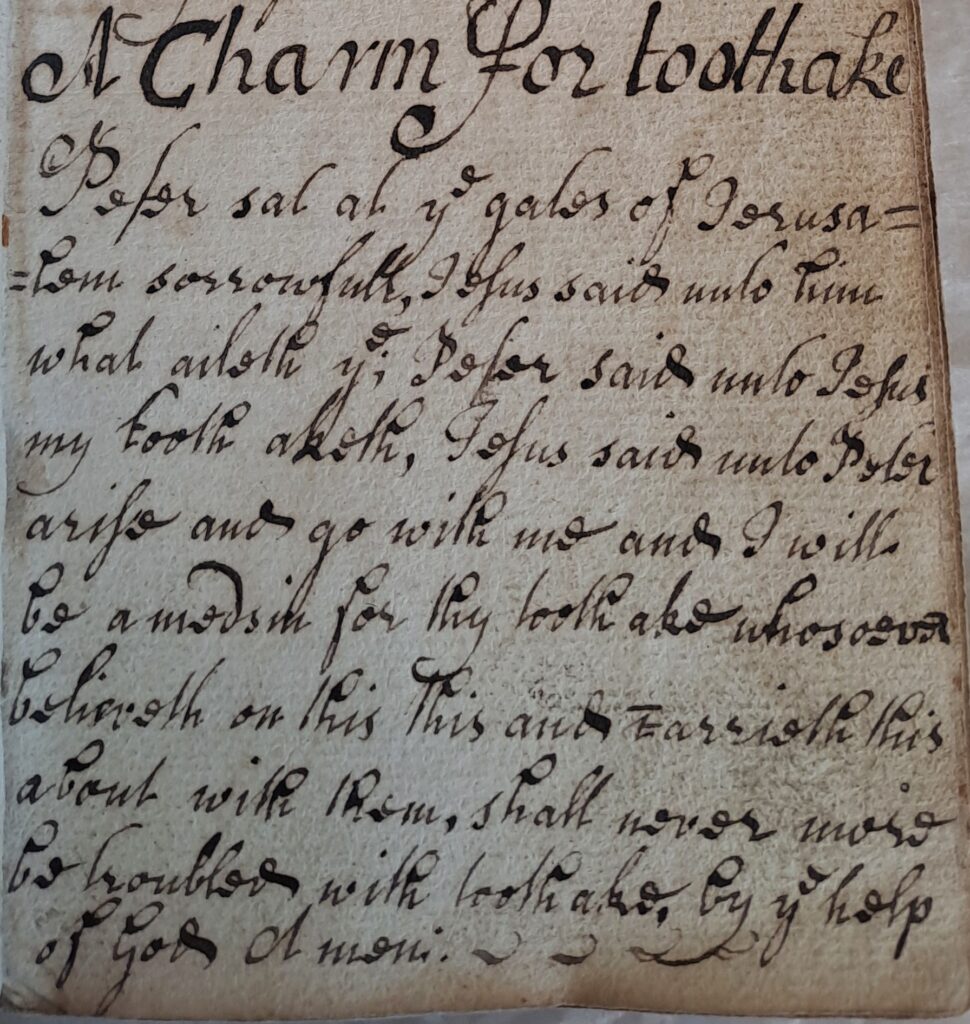

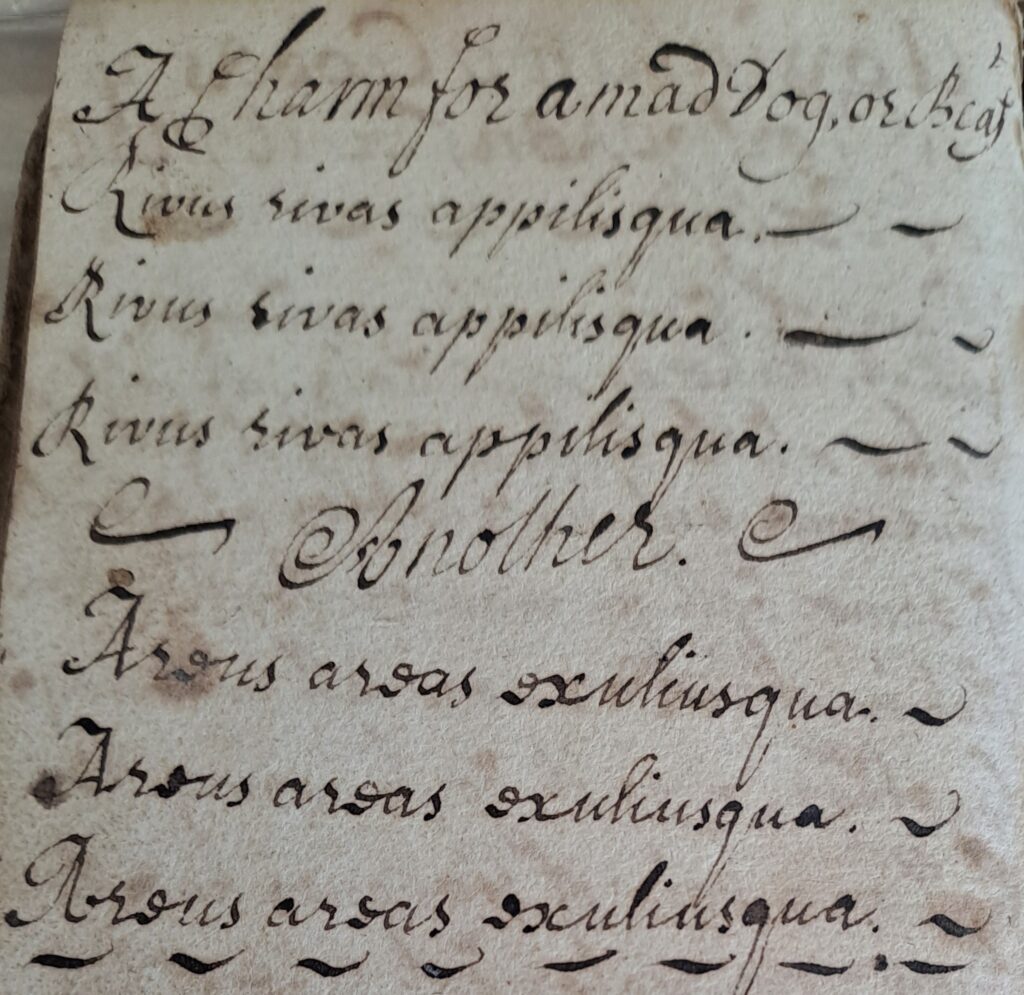

When herbal remedies fail, there are always prayers or charms that can be recited. And here is where it could be interpreted as being a spell book. Lambert offers a religious “charm for toothache” which starts with “Peter sat at [the] gates of Jesusa… sorrowfull” with toothache and Jesus says “I will be a medsin [medicine] for thy tooth ake [ache]… by [the] help of God Amen”. This toothache charm with Jesus comforting or curing toothache-afflicted (Saint) Peter is known as the super petrum charm. Examples of this oral and written charm have been found across Europe, commonly dating to the Medieval period but some as recent as the 1800s. There is also “A charm for a mad dog, or beast” in Latin with the repeated phrase “Rivus rivas appilisqua” referring to river banks, possibly meaning ‘the river banks are scattered’.

Some of Lambert’s charms offer protection against witchcraft. As I presented in previous displays of superstitious objects at Bolling Hall, during the witch-craze of the Early Modern period (1500–1700, and into the 1800s in some areas), people turned to ‘magic’ or ‘counter-magic’ using charms and amulets for protection against witchcraft.

To find out more about this and superstitious objects in our collection, you can read this blog.

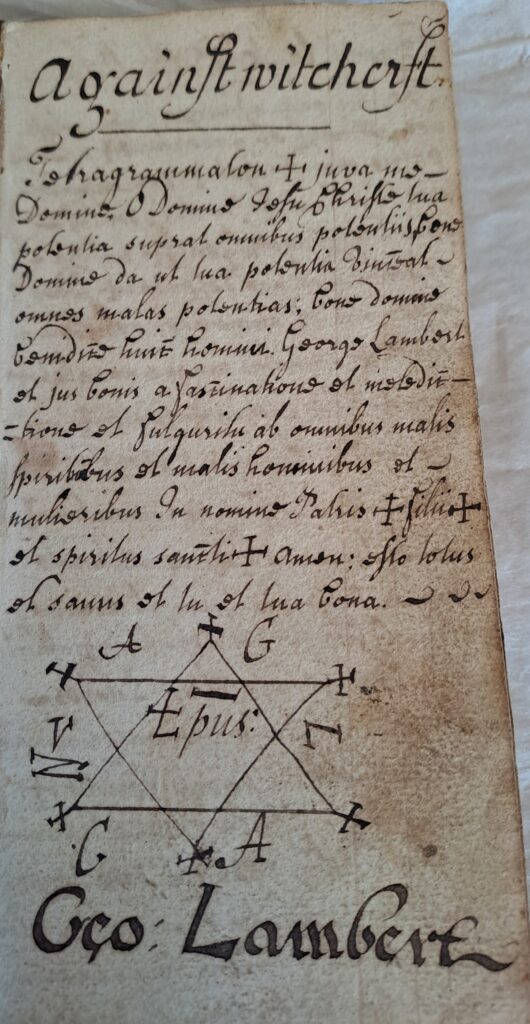

One of Lambert’s charms “against any goods [that] forspoken, be it man or beast” involves boiling and burning a pin-filled ball of hair. The word ‘forspoken’ means charmed, bewitched or cursed. A prayer-like charm “against witchcr[a]ft” in Latin asks “O Lord Jesus Christ” to “direct his power over all wills. Lord, grant that his power, may overcome all evil wills. Lord, Lord, help this, George Lambert…” from “all evil spirits and all evil men and women. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, Amen…”. Another says “The cross of Christ be always with thee [and] the cross of Christ beat down every evil; both from thee and from thy goods and children. Fiat fiat fiat [Latin phrase meaning ‘let it be’] Amen George Lambert”.

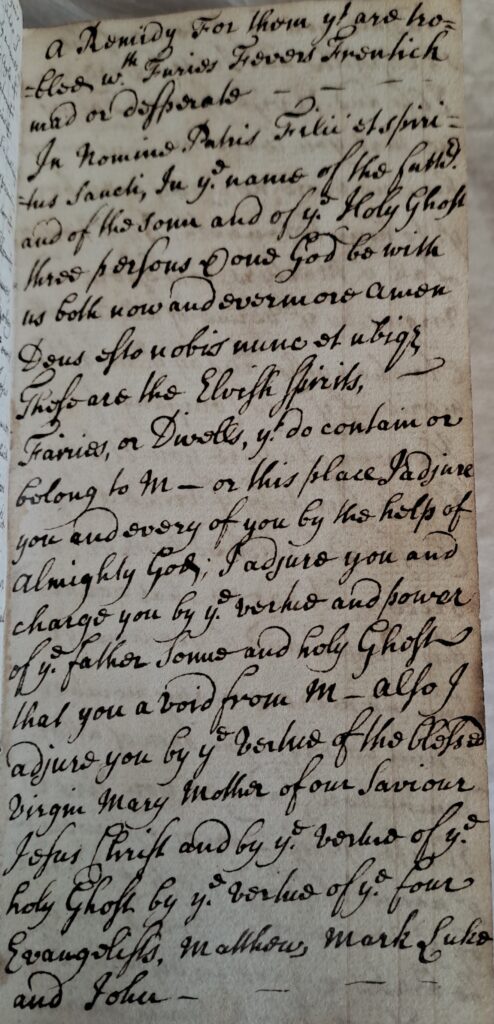

As well as witches and witchcraft, Lambert was spiritually defending himself against other supernatural entities: elves, fairies and devils! Across four pages he records “a remedy for them [that] are troubled [with] fairies fevers from which mad or desperate”. Lambert invokes names of various religious/biblical figures while repeating “I adjure you elves, elvish spirits, fairies and divells” to “leave m[e] and annoye him no more nor any member [that] to him belongsth” “by night nor by day, sitting, nor standing, sleeping nor wakeing at home nor abroad” “avoid from this person without any further delayes”.

The mention of elves and fairies may seem odd as we see them today as benevolent creatures. Religious beliefs of the Stuart period (early 1600s to early 1700s) meant that supernatural entities such as witches, ghosts, elves and fairies were seen as malevolent and in league with the Devil due to their ability to use magic, disguise themselves, trick and deceive.

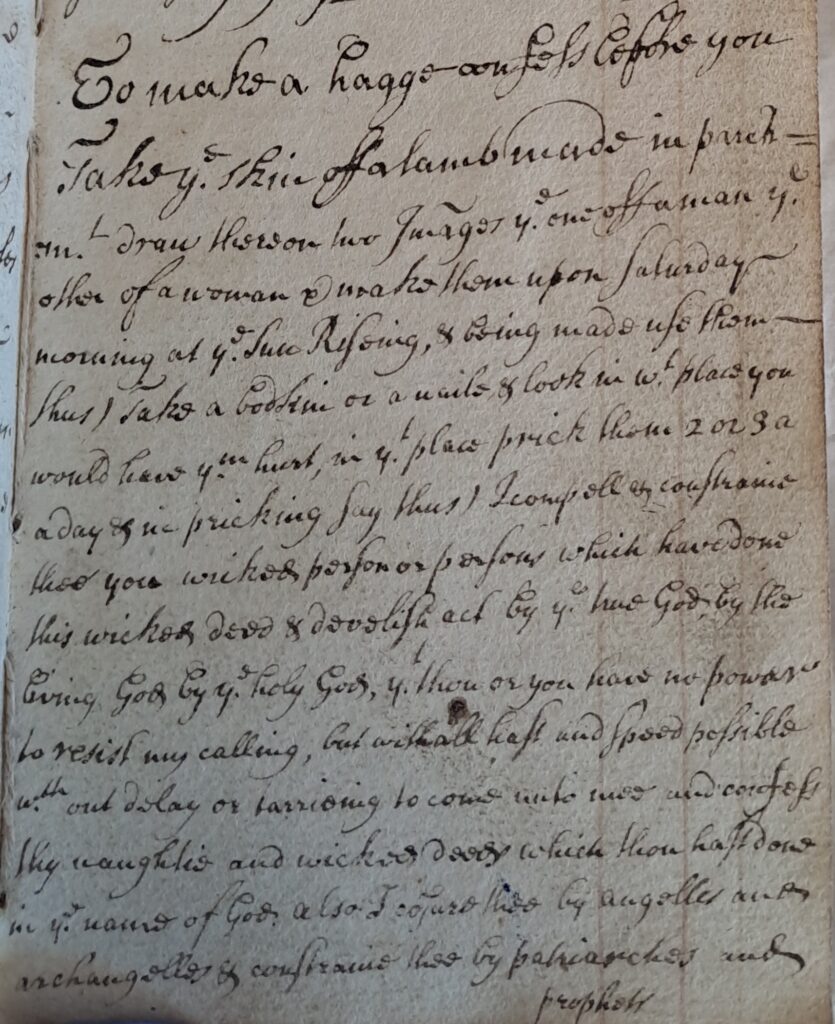

As I was going through Lambert’s book, I turned to this page and as my eyes were drawn to certain words, a chill ran down my spine. What clearly stood out were the phrases “hagge confess”, “take a bodkin” and “prick them”. During the Early Modern witch-craze, it was believed that witches had bodily marks, the Devil’s marks, which were signs that they had made a pact with the Devil or where they fed their demonic familiars from their own bodies. ‘Witch-finders’ used bodkins/bodikins or needles to prick people accused of witchcraft in these areas and if they didn’t bleed, it was considered proof. In 1650, Mary Sykes, the accused witch of Bowling, Bradford, was inspected for witch-marks – read more about this local case here. Lambert’s witch-finding method is:

To make a hagge confess before you take [the] skin of a lamb made in parchm[ent]. Draw thereon two images [the] one of a man [the] other of a women & make them upon Saturday morning at [the] sunrising & being made use them. Thus take a bodkin or a nail & look in [what] place you would [them] hurt in [that] place prick them 2 or 3 a day & in pricking say thus I compel & constrain thee you wicked person or persons which have done this wicked deed & devilish act by [the] true god by the loving god by [the] holy god, [that] thou or you have no power to resist my calling, but withall hast[e] and speed possible [with] out delay or tarrying to come unto me and confess thy naughtie and wickedness which thou has done in [the] name of god also I conjure thee by angelles and archangelles constraine thee by patriarches and prophets….

It then continues onto a second page where various biblical figures are called upon and then it ends saying “And having thus done twice or thrice a day [the] evil person shall not take rest nor sleep until he, or she, hath seen you to crave pardon at your hand”. After fully deciphering it, I was relieved that it wasn’t instructions on how to physically torture people accused of witchcraft. This recommends making an effigy of the ‘wicked’ person/s by drawing an image of them on lamb skin parchment and sticking pins into it which will compel them to seek a pardon/forgiveness and confess. Effigies or poppets were common in folk customs of the time to protect, heal or promote love, or contrastingly to cause harm. One might consider creating an effigy of a person to stab with pins to torment them as witchcraft itself. This is a good example of how ‘counter-magic’ measures were not seen as witchcraft to those practicing it, and how the line between good magic or evil witchcraft was grey or blurred, based on interpretation or intent. A protective charm could be interpreted by others as a curse (as might have been the case with Bradford’s Mary Sykes); a healing herbal concoction could be seen as a poisonous potion if ineffective; a protective poppet as an evil effigy.

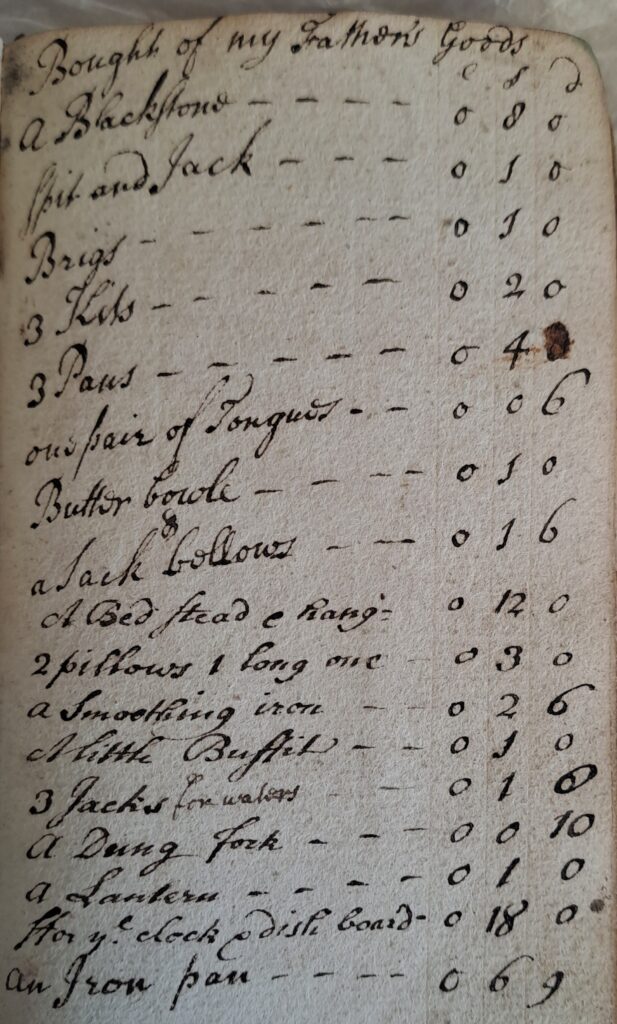

When he wasn’t making effigies, Lambert kept on top of his financial accounts. A double page has the telltale three columns for accounting where typically the right-hand side columns are for pence, centre columns for shillings and left-hand side columns for pounds. It lists individuals by their first name initial and full surname with either 1 or 2 in the pound column, but it is unclear if this is credit or debit. Further on, there is another double page of accounts with the right-hand column labelled ‘d’ for pence, the centre column labelled ‘s’ for shillings and left-hand column labelled ‘li’, an abbreviation of the Latin word libra meaning pound. It shows purchases, for example, “Bought of James Lambert four chairs” for 5 shillings; “bought att a sale att Bingley half a dozen of chairs” for 14 shillings and 2 pence. It also lists objects “bought of my father’s goods” including “a blackstone”, “spit and jack”, “a bed stead”, “2 pillows 1 long one”, “a dung fork” and “a lantern”.

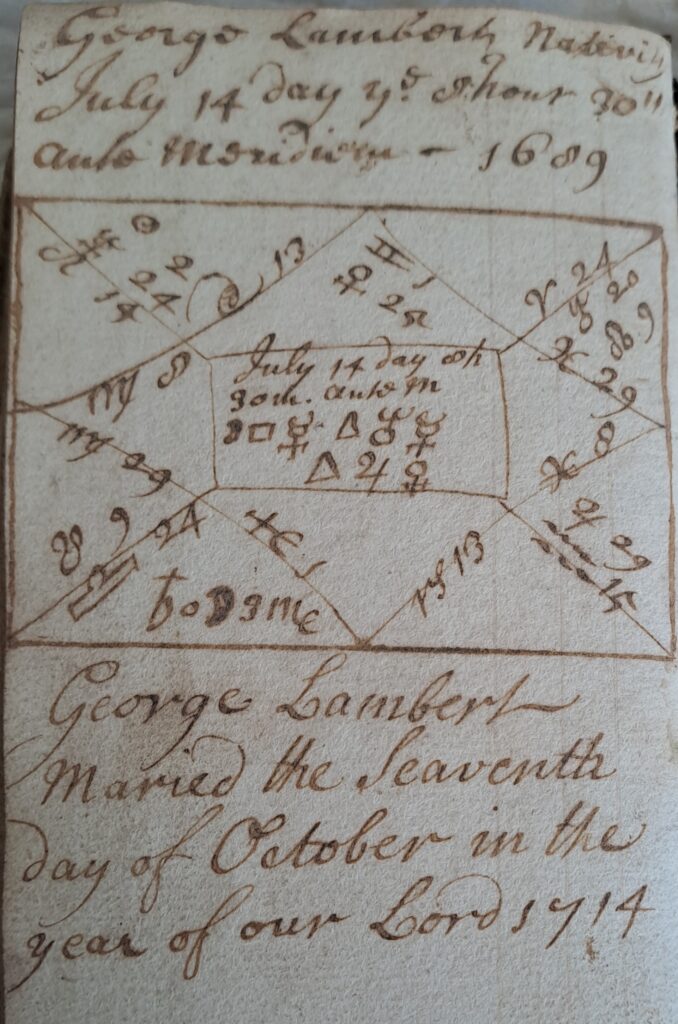

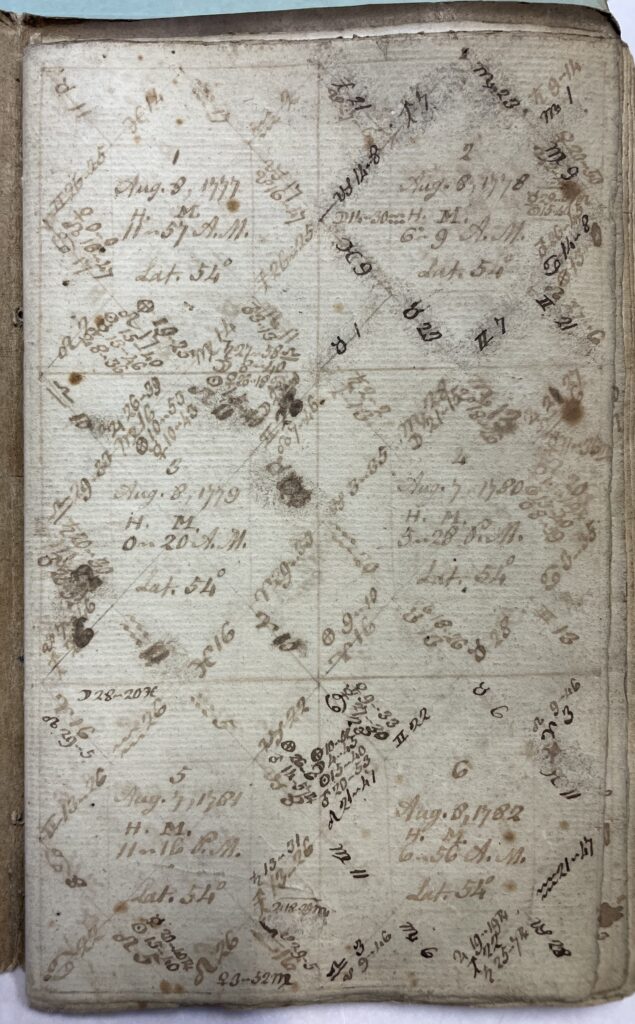

Let’s move onto something less familiar with the symbols and drawings. Under a Latin charm against witchcraft is a six-point star with letters and markings around it. The same star illustration or chart appears again under another Latin charm against witchcraft. Further on in the book, Lambert records biographical information about himself and family members illustrated with more of these star charts which are more complex than the earlier ones. He wrote “George Lambert Nativity July 14 day [that] 9 hour 30” ante meridiem [before midday] – 1689” and the illustration shows a centre square that repeats the date and time with twelve triangles around it. Symbols and numbers are written in the triangles and along the lines.

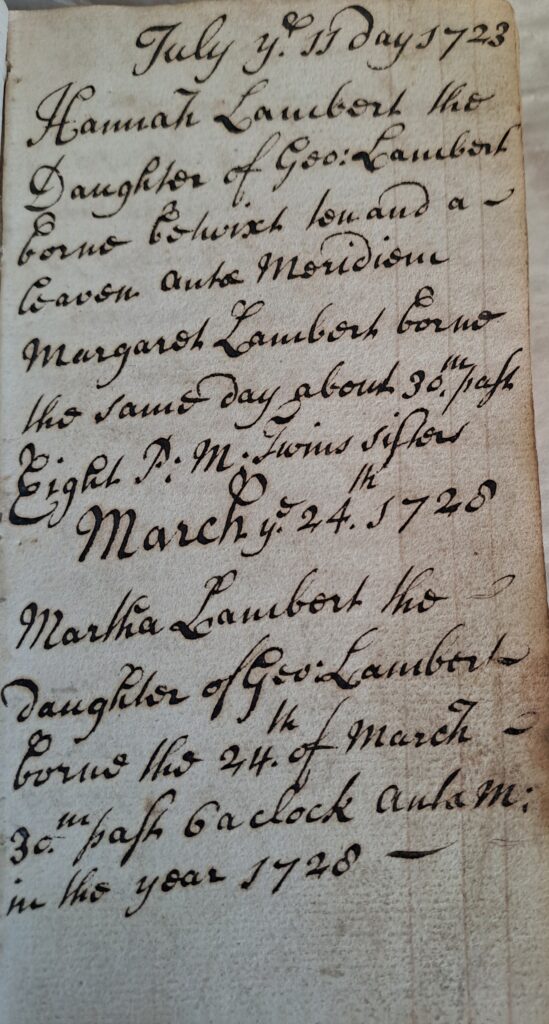

The following page says “The nativity of Ann Lambert the daughter of George Lambert born October the 6 day 15 m[inute] before nine o clock ante m[eridiem] anno domini 1716” with a star illustration. Then “The nativity of Mary Lambert [the] daughter of George Lambert borne January the eleventh day 15m[inute]: past 8 o clock am ante m[eridiem]: 1719” followed by a star chart. I came to understand that these are nativity or natal charts which shows the constellations and planets as they were positioned at the date and time of someone’s birth. The twelve triangles are the houses of astrology, the symbols are the zodiac signs, and the numbers may refer to the degrees between them. Natal charts were used to predict someone’s health, wealth and life events.

We have another book in our collection that has astrological charts. Abram Shackleton of Braithwaite kept detailed meteorological diaries or weather registers from the late-1700s to the mid-1800s (museum accession numbers m220.1 to m.220.6). As well as recording the weather and rainfall, Shackleton produced astrological charts for specific days.

Craven Museum in Skipton has in its collection a book that belonged to Timothy Crowther of the 18th century that contains astrological charts similar to Lambert’s. Due to Crowther’s reputation as a ‘cunning man’ or ‘wizard’, historians originally interpreted Crowther’s book as a spell book, but in more recent years it has been reinterpreted less as a spell book and more as a commonplace book or diary giving an insight into folk magic and astrology.

Using the biographical information Lambert recorded about himself and family members, I set about looking into the Lambert family ancestry. Lambert recorded that he was born on 14 July 1689. In the Kildwick-in-Craven baptism register of 1689, there is a record in Latin for “Georgius Lambert filius Guiliemi et Annæ Lambert de Gilgrange” on 28 July 1689. So, George Lambert parents were Gulielmi (Latinised version of William) and Anna Lambert of Gil Grange. As civil/central records of births were not compulsory until the late 1800s, we rely on parish records of baptisms from this time; babies were usually baptised within a fortnight, if not sooner, of being born. As Lambert wrote his name in the book with the date 1707, that would make him around 18 years old at the time when he possibly started it.

Lambert also recorded his marriage, “George Lambert maried the seaventh day of October in the year of our Lord 1714” but doesn’t name his wife. I was able to find the marriage record of George Lambert to Hannah Gawthorpe in 1714 in Otley. Together they had several children during their marriage. Lambert recorded their birth dates, with natal charts for a couple, and sadly also documented their death dates. Ann Lambert was born in 1716, Mary in 1719, twins Hannah and Margaret were born in 1723 and Martha in 1728. Hannah passed away in 1737 and Margaret in 1739. I was able to find baptism and burial records for the children that corresponded with the dates Lambert recorded. The records named George Lambert, of Howden in 1723 and of Gil Grange in 1728 as their father and described him as a “husbandman”. The places attached to Lambert in these records, such as Otley, Kildwick in Craven, Howden and Gil Grange place him locally in the Craven District.

Somebody recorded Lambert’s death for him in his book: “George Lambert died the third day of September in the year 1751 about elaven a clock before noon”. The Kildwick burial register records his burial three days later, “George Lambert of Gil Grange Yeoman” on 6th September 1751. By his death he had advanced from a small tenant farmer or landowner as a “husbandman” to a “yeoman” which had a higher status as a freeholder with larger property/land, and they often held civic roles. If Lambert was a husbandman and then yeoman, this might account for why he recorded animal husbandry cures if he owned animal and raised livestock.

While I don’t think we will ever rename the book from the ‘Lambert spell book’ to the ‘Lambert commonplace book’, now we have demythologised it we can feel a bit more comfortable when researchers request an appointment to view it or other museums ask to borrow it… but I’ll keep the warnings on its record and box just in case.

3 Responses

As always a really interesting read Lauren

Very interesting Lauren really enjoyed reading this.

Would love more articles please