Dr Lauren Padgett, one of our Assistant Curators, shares how a recent enquiry let us take a closer look at a 251-year-old recipe book by a Bradford gentlewoman in our collection, giving us a taste of 18th-century food history.

The enquiry

In April 2023, local and family historian Mary Twentyman contacted Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ Collections Team explaining that they had seen a Bradford Observer newspaper article from 1950 about a cooking demonstration at Bolling Hall Museum and an 18th century recipe book by “Anne Rookes… daughter of ‘Squire’ Edwards Rookes Leeds, of Royds Hall…”.[1] Mary was trying to locate the recipe book. A search of our collections database showed that we have a book that fit that description. Acquired in 1934, its record says:

Manuscript book of recipes… mostly in the writing of Ann Rookes, but there is also another hand; 144 pages of recipes of various types; Ann Rookes was apparently a member of the family who lived at Royds Hall; some of the recipes in the book are from local people. 1772.

After retrieving the book from our reserve stores, Mary was invited to Bolling Hall Museum to view it the following week.

Household recipes

18th century manuscript recipe, or ‘receipt’, books contain handwritten recipes, usually compiled and kept by upper-class women who oversaw their kitchens. They would approve daily meal plans and dinner party menus with their cook or housekeeper. They wrote down favourite or family recipes for posterity and for the kitchen servants to follow – although recipes were probably read aloud to them due to lower literacy levels amongst domestic servants. Often other family members and generations added their recipes over time. Some include herbal remedies for ailments.

Commercially printed cookery books would have been consulted too by wealthy women and influenced food fads. In the early 18th century, these were often complicated to follow with French phrases and complex cookery terms. This led Hannah Glasse to write her highly popular book, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747, with “the lower sort” in mind. Glasse used plain instructions and simple terms so recipes were easy to follow by servants. “… every servant who can but read, will be capable of making a tolerable good cook…”, wrote Glasse in her preface. By the mid-19th century, printed cookery books contained detailed easy-to-follow recipes with ingredient lists (like Modern Cookery for Private Families by Eliza Acton in 1845) and exact measurements, and some included housekeeping and etiquette advice (like Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management in 1861).

‘Gamekeeper and Cook’ by David Wilkie, oil on panel (153:1959.7). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

Researching the Rookes

Mary’s initial enquiry cast doubt on the Bradford Observer’s claim that the recipe book belonged to the daughter of ‘Squire’ Edwards Rookes Leeds of Royds Hall (in Bradford). Edward Rookes changed his surname to Leeds (also spelt as Leedes) in 1740 when he married Mary Leeds. But his name was, and still is, stylised as variations of Edward Rookes-Leeds or Rookes Leedes.[2] Edward and Mary Leeds had four daughters, one of which was an Ann (1752 – 1798). Ann married Rev. Jeremiah Smith so she would have been known as Ann Leeds then Ann Smith. So it doesn’t seem likely that she is our Ann Rookes. Mary proposed that the recipe book was written by an alternative Ann Rookes who was linked not only to Royds Hall (by marriage) but another great hall and estate in Bradford: Esholt.

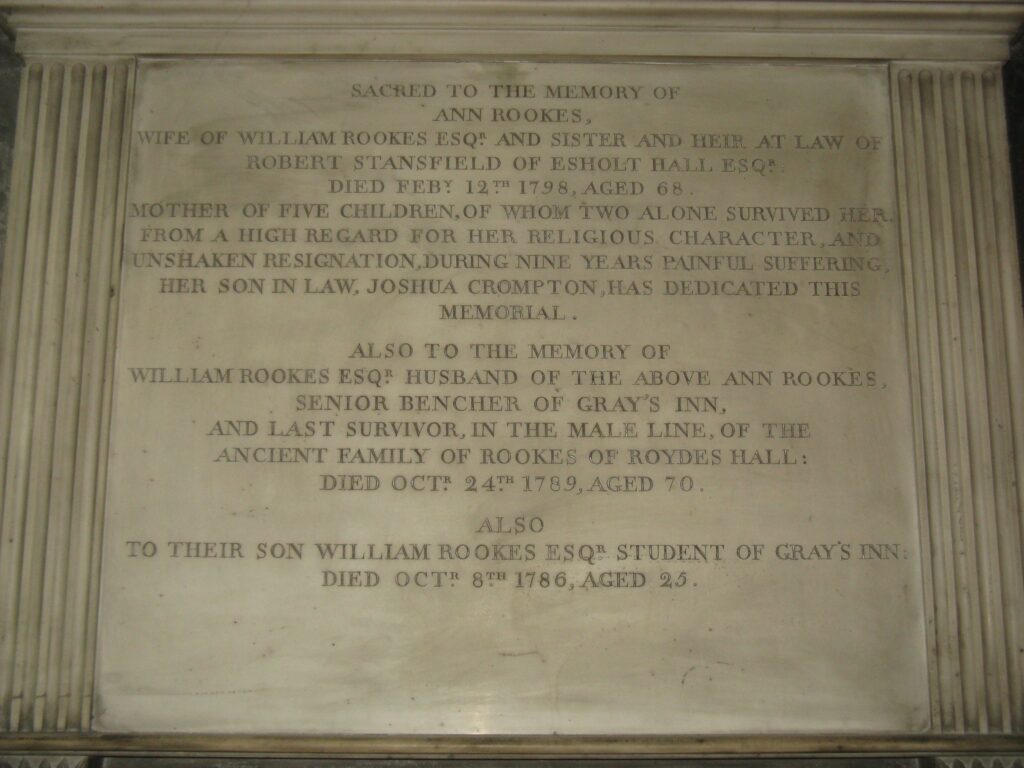

Ann Stansfield was born on 27th August 1729 and married William Rookes (born 1719, died 1789) of Royds Hall in 1758. William is Edward (Rookes) Leeds’ brother. Ann’s brother, Robert Stansfield, purchased Esholt Estate, including Esholt Hall, in 1755. In 1772, when Robert died with no children, Ann inherited the Estate. She died at Esholt Hall on 12th February 1798, aged 68. I have been unable to locate a portrait of Ann; her memorial in St. Oswald’s Church, Guiseley, says:

Sacred to the memory of Ann Rookes, wife of William Rookes Esqr. and sister and heir at law of Robert Stansfield of Esholt Hall Esqr.:

Died Febr. 12th, 1798, aged 68. Mother of five children, of who two alone survived her.

From a high regard of her religious character, and unshaken resignation, during nine years painful suffering, her son-in-law Joshua Crompton, has dedicated this memorial.

Rookes memorial, St. Oswald’s Church, Guiseley. Photo taken and kindly provided by Mary Twentyman, 2023.

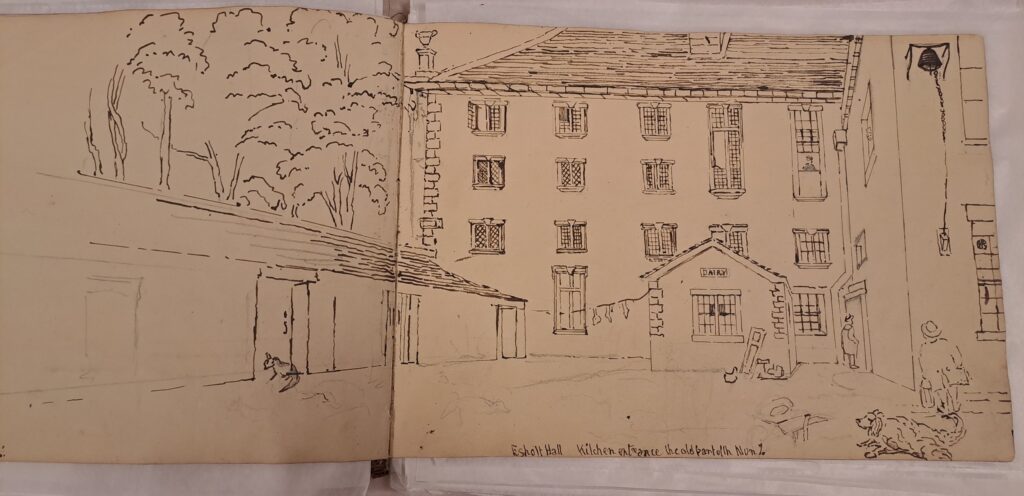

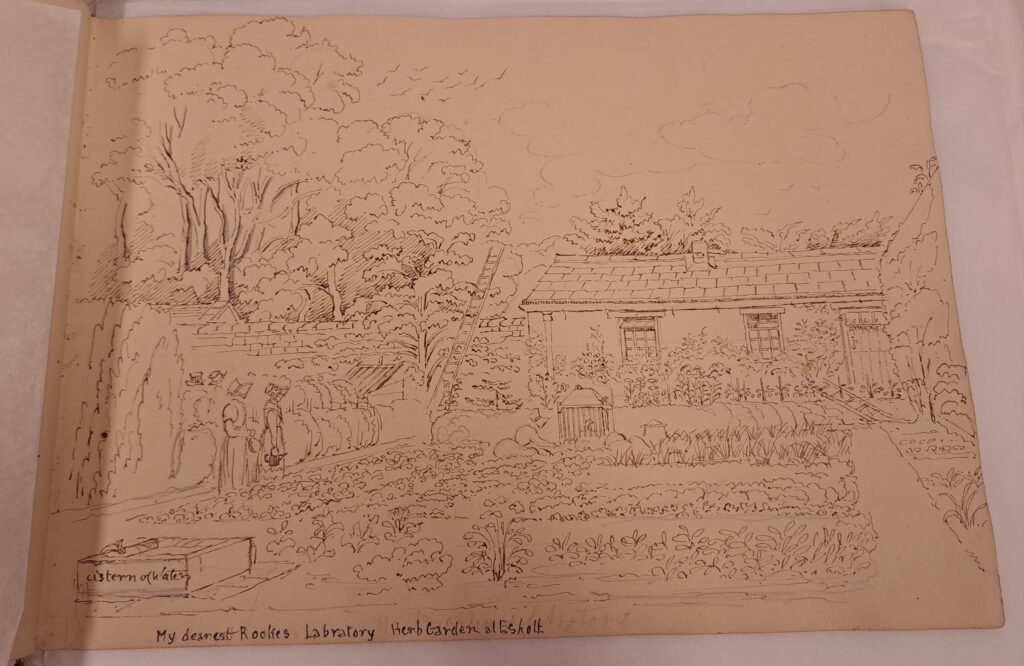

Interestingly, in Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection is another book belonging to this family – a 19th-century sketchbook (H.3/1985). It seems to have been started in 1824 by Joshua Crompton, Anne’s son-in-law, and passed onto his son (Anne’s grandson) William Rookes Crompton-Stansfield and then William’s nephew, Col. William Crompton Stansfield. It includes drawings and paintings of mostly Esholt Estate and Hall. Some have been used to illustrate this blog.

Front cover of ‘Esholt Hall’ sketchbook (H.3/1985). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

‘Esholt Hall 1829’. ‘Esholt Hall’ sketchbook (H.3/1985). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

Ann’s Recipes – “Approved Ones”

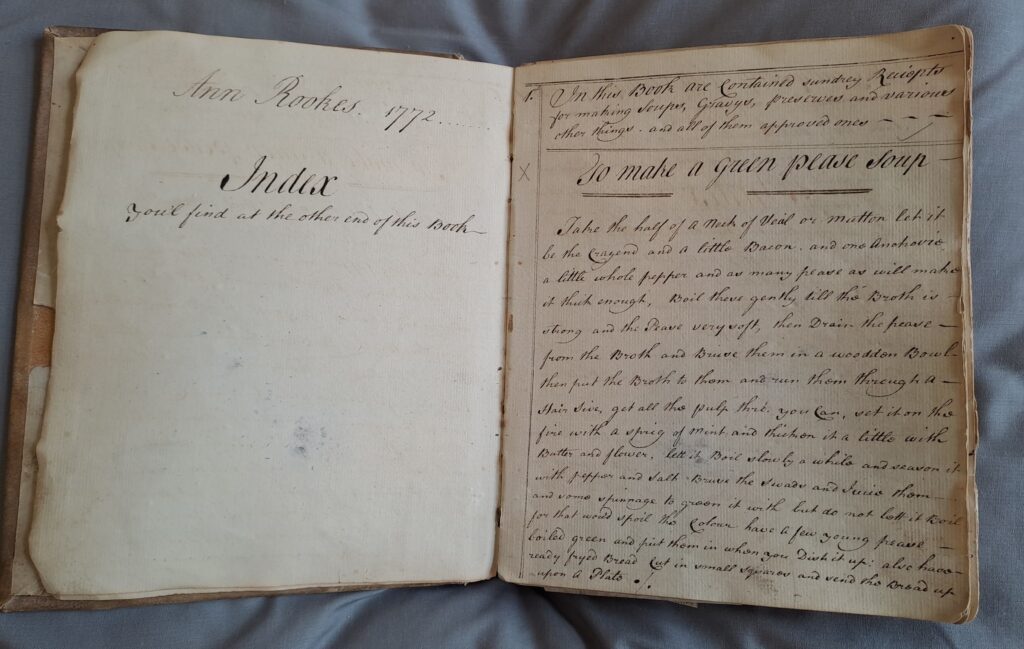

When quoting the recipe book, I have kept Ann’s original spelling so some words differ to our modern spelling. In Ann’s handwriting, the recipe book’s title page says “Ann Rookes 1772”. 1772 is the same year that Ann inherited Esholt Estate. Ann helpfully included an “Index” which “you’l find at the other end of this book”. The first page says “In this book are contained sundrey reciepts for making soups, gravys, preserves and various other things, and all of them approved ones”. The word “approved” appears often in 18th- and 19th-century recipe and cookery books to signify that the recipes were tried and tested by the author. The first recipe is “green pease soup” made from the “cragend” of “veal or mutton”, “a little bacon”, “one anchovie, a little whole pepper and as many pease as will make it thick enough”. Ann warned “do not lett it boil for that would spoil the colour” and her serving suggestion is to “dish it up” with “fryed bread cut in small squares”.

Title page and recipe 1. Ann Rookes’ recipe book (10/1934). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

Some recipes are attributed to other named individuals. Handwriting changes at times suggesting they wrote their own recipes. Mary did some research into the contributors and highlighted Ann’s family members. Mrs Crompton, who provided a lemonade recipe, is probably her daughter, Ann Marie Crompton. Mrs Leeds’ gingerbread recipe could be her husband’s step-mother’s, Henrietta Leeds’. Mrs M Rookes’ “macroons” recipe may be her sister-in-law’s, Mary Rookes’.

There are recipes to suit all palates: meat and fish dishes (from “stew pidgeons” to lobster); vegetarian options (stewed mushrooms, cucumbers and celery); savoury cuisine (“fricasy rabbit, chicken or turkey”); sweet courses (“good common cheesecakes”, “bread pudding with dryed cherries in it or currants”, “carrit pudding” and “plumb cake”); and beverages to wash the meals down with (ginger tea, “orange wine”, “cowslip wine”, “green gooseberry wine” and two mead recipes).

Some recipes are more appetising than others as eating habits have changed since the Georgian period. Dinner guests today might not appreciate being served a plate of “calfhead hash” or “brain cakes”, and may politely decline Ann’s dish of “briole[d] eelles”, even if they are served in “melted butter and crisp sage leaves”, and Mrs Rockett’s “oyster sausages” – made from “a pint of oysters” and described as “sausage meat” and “very good to stuff. . . a turkey” with.

‘Poultry Yard at Esholt Hall’. ‘Esholt Hall’ sketchbook (H.3/1985). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

Ann details cooking various methods and techniques, such as how “to clarify butter”, and how to pickle and preserve vegetables (“pickle girkins”, “sliced cucumbers”, walnuts, cabbage) and fruit (apricots, barberries, quinces, “damsins” and “oranges whole or in halfs”). At the end of a recipe for a “Queen cake”, Ann recommends that “The best way of beating the whites of the egges to a high froth, in with half a dozen quills split sundry times at the ends, and tyed up together”.

Not for any vegetarians, vegans or the faint hearted, she provided thorough instructions on how to dress (prepare) raw meat. In order “to roast a pigg”: “first clean it well from hair and take out the intralles, and wipe the belly well out with a cloth. . . then split it and lay it down to the fire. . . when roasted enough cut the head of. . . take out the brains”. Not wasteful, Ann then suggests that for “the sauce for the pigg, bruise the brains”, add herbs, melted butter and “gravy which comes from the pigg”.

‘Esholt Hall Kitchen Entrance’. ‘Esholt Hall’ sketchbook (H.3/1985). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

A few recipes stand out as quintessence 18th-century cuisine. The “catchup” (ketchup) recipes are not like the bottled red ketchup consumed today; ketchup wasn’t tomato-based until the 19th century. Ann’s bottled ketchup recipe is typical of the 18th century, made from mushrooms and seasoned with “whole black pepper a little clove pepper mace raising ginger, and a few cloves and salt if not savoury enough”, boiled to concentrate the flavour “till the strongth is come out”, “when cold bottle it for use”. Mrs Ward offered a recipe for “white catchup” made from white wine vinegar and anchovies. Mrs Hawkesworth provided her “walnut catchup” recipe. Mrs Lobley recommended her “cucumber catchup”.

Another interesting recipe is “Lills pickle in imitation of the Indian pickle”. Recipes for English versions of South Asian and Indian pickles, known as piccalilli, appeared in the 18th century using spiced seasonal vegetables. Ann’s piccalilli is “cabage colliflower carrots brokeolo turnips apples” pickled in ginger, “garlick” “handful of mustard seed” “small handful of long pepper” and “turmerick powder”.

Photo of spices on display in the Warm Kitchen at Bolling Hall Museum, Bradford District Museums and Galleries.

It wouldn’t be a Georgian recipe book without mock turtle. In the 18th and 19th century, thousands of live turtles were imported from the West Indies to Britain so the upper class could savour turtle soup. This fashionable dish, which became a symbol of wealth, was an upper-class staple from the mid-1700s into the mid-to-late 1800s. For those who couldn’t afford turtle meat (or when turtles were in short supply due to overfishing), mock turtle was prepared and served instead. This became a classic dish in its own right. To imitate turtle’s texture and flavour, mock turtle was made from calves’ brains seasoned with herbs and typically cayenne pepper. Ann’s book has different recipes for “mock turtle”. Both consist of boiled calf’s head and are served with boiled eggs and “force meatballs”, which are stuffing balls made from mushrooms and herbs. Mrs Lobley has also provided instructions on how “to dress a calfshead like turtle”.

Photo of the Georgian dining room at Bolling Hall Museum, Bradford District Museums and Galleries.

There are also medicinal recipes to help with ailments, such as “gripes in the bowells” and the “common cough or hoarsness”, with details of how to make “a most excellent ointment for the eyes” and a poultice for “swelling that is inflamed”. There’s “a good receipt for the ague” (fever) made from wormwood – the wrong quantities of which could be toxic, and “medicine for the jaundice” made from powdered “rhubarb” and “Castilo soap” – which is probably the olive oil-based soap Castile, used to clean laundry and also taken medicinally. “Doctor Hodgsons gout cordial” contains raisins, fennel seeds, saffron, liquorice, rhubarb and brandy, while “Doctor Hills receipt for the scurvy” is “half of pint… twice a day” of a juice made from “fresh root of the great water dock”. Mrs Wakes’ “receipt for a consumption” is made from a stomach-turning “pint of snails” and “pint of earth worms”. Mrs Lobley’s “laxative medicine” has prunes and brandy in it. Mrs Warters provided a recipe for “pains in the bowels… or loosness” and another for “when the bowels are full of wind or any degree of hysterical affection is present”. There is also a “cure for the red water in cattle”; red water disease (so called as one symptom is red urine) is transmitted by ticks and can be deadly in severe cases.

‘My dearest Rookes laboratory herb garden at Esholt’. ‘Esholt Hall’ sketchbook (H.3/1985). In Bradford District Museums and Galleries’ collection.

This manuscript of recipes has served us a tantalising taste of 18th-century food history and given us a flavour of the eating habits of Bradford’s upper-class society. We are grateful to Mary Twentyman for her initial enquiry and generous research. Mary is a local and family historian affiliated with Bradford Family History Society and Low Moor History Group, part of South Bradford Local History Alliance.

Has this whet your appetite? Visit Bolling Hall Museum this summer (2023) to see our exhibition ‘A Bradfordian Banquet’ about the history of food and eating. Discover world-wide influences that have shaped our diets since the Middle Ages and the way that we have adapted what we eat due to industry, war and travel.

As part of the ‘A Bradfordian Banquet’ exhibition, we are collecting recipes. Do you have a favourite family recipe? We’d love you to share it with us. Please contact us on our socials or email collections@bradford.gov.uk.

Photo of the food timeline in the Housebody, as part of ‘A Bradfordian Banquet’ exhibition, at Bolling Hall Museum, Bradford District Museums and Galleries.

[1] ‘A page from Anne Rookes’ recipe book when our waistlines did not seem to matter’, Bradford Observer, 18 May 1950.

[2] A petition to the House of Lords in 1742 asked that they “bring in a Bill, to enable him to take and use the surname of Leeds only”. Journal of the House of Lords, 1742, vol. 26, 16 Geo. II. p. 183.