Our Assistant Curator, Kirsty agreed to write this blog, sharing an insight into some more of the stores currently being told in the Keighley’s War Exhibition, on at Cliffe Castle Museum until the 18th November.

She writes:

Over the past four years Bradford Museums and Galleries has commemorated the centenary of the First World War with a series of exhibitions, community projects and events. This year an exhibition at Cliffe Castle Museum has focused on the role that Keighley and its people played in this war.

Within the exhibition Keighley’s War we have aimed to give our visitors an idea of just how deeply the war penetrated the lives of Keighley residents by focusing on a selection of people and key objects from within our collections.

When looking at the concept of exhibitions and displays we always need to ensure that we have two key things: a story and objects. It is the magical combination of these two elements that complement each other and create something that we hope to be both informative but also visually interesting for our visitors.

We had bountiful sources of information on Keighley’s role in the First World War, from books, newspaper articles, our museum records and the research carried out by the group Men of Worth.

From these sources it became apparent that a key role that Keighley played was with its provision of a War Hospital and a series of auxiliaries:

Keighley had done well for the country – first in making cloth for the troops, in making munitions; and then in making machines for constructing those terrible implements of war. They had done their duty in that respect. Now they were to repair the damages which instruments of war had caused.

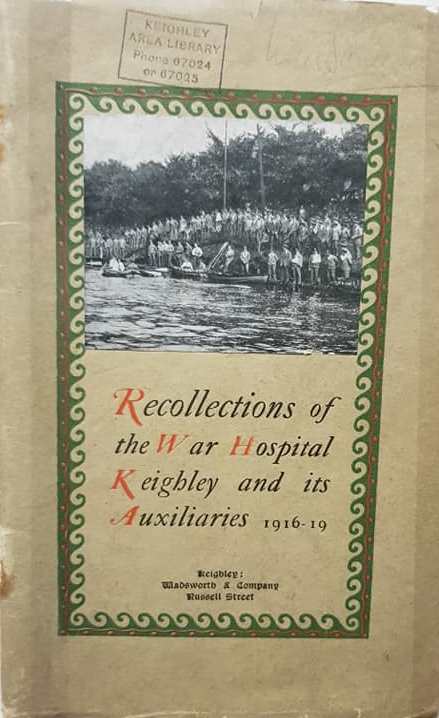

Recollections of Keighley’s War Hospital and its Auxiliaries

The Keighley and Bingley Joint Hospital initially opened its doors in February 1897 as an isolation hospital. It was set in a beautiful location on the slopes of Rombalds Moor, on the left bank of the River Aire, with open verandas, where patients were able to enjoy the fresh air.

On 12 January 1916, the Keighley and Bingley Joint Hospital Board held a meeting. It was proposed at this meeting that the Joint Hospital at Morton Banks and all of its equipment be offered to the War Office for the accommodation and treatment of sick and wounded soldiers. The decision across the board was unanimous and on 5 April, 1916, the Army Council gratefully accepted the proposal and the Keighley and Bingley Joint Hospital became the areas main War Hospital.

The demand for the hospital was so great that on 3 April 1917, the current Mayor, Frederick Butterfield, owner of Cliffe Castle and his predecessor Mr W. A. Brigg decided to look at the possibility of building an extension. At a preliminary meeting Frederick said that:

During the past year £12,500 had been raised for hospital purposes while £15,000 had been spent. These sums were worthy of the district and also of the cause for which they were raised, but, let it not be said that at such a time as this Keighley and neighbourhood are backward in providing for our stricken Soldiers, and let it not be said either that £15,000 or even £20,000 is the measure and the limit of our charitably patriotic efforts.

Four months later the extensions were completed.

The Hospital was seen to be so proficient in certain areas that it became a centre for American Red Cross surgeons to see the latest developments in military surgery and attend lectures on modern methods of treating gas poisoning, gas gangrene and wounds.

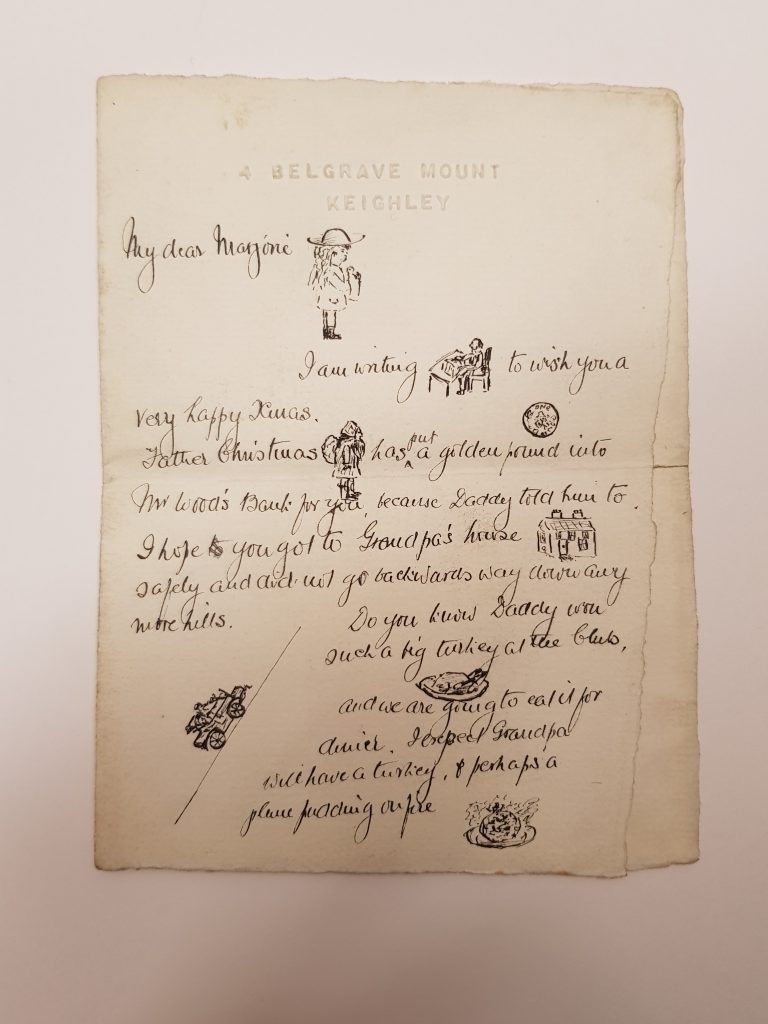

One of the most intriguing set of objects in this display is a selection of letters sent from a soldier who served as part of the Royal Army Medical Corps to his daughter Marjorie. The letters have been sent from the soldier’s numerous posts including France, Masham and Keighley. In his letter sent from Belgrave Mount, Keighley he tells his daughter how: The nurses at the dispensary are always sending you their love and asking when they will see you again, suggesting that the daughter Marjorie had also visited Keighley at some point.

Accompanying the letters is a really interesting miniature portrait of the soldier set in the back of a military button. The objects allow us quite an intimate look into this family’s life and experience during the First World War and their time in Keighley but the identity of the soldier is still a mystery to us.

An important thing to remember is that it wasn’t just the proficient medical care that made the War Hospital such a success. The hospital catered for the soldiers medical needs but various small organisations had been created around the hospital to ensure the comfort of the men.

The majority of the wounded soldiers arrived into Keighley by train; from here the men would travel, by foot, or by private cars which had been converted into ambulances. On exiting the trains and making their way up the station slope, each new arrival would receive a kindly greeting from Mrs Scatterly and a packet of Golden Flake tobacco from Mr Tom Crabtree.

There was a group of ladies who visited the hospital to provide company for the men, and another group of women ran a canteen at the hospital. A Welfare Committee was created where 440 voluntary women served a special tea for the men once a week; the funds for this were raised by a group of women who went house to house collecting a penny a week from all of those that were willing. A committee of women met daily to sew and prepare a vast array of medical provisions including bandages, pneumonia jackets and swabs. In June 1916, the Wounded Soldiers’ Comfort Committee was founded; they opened a depot where gifts of clothing, eggs and vegetables could be dropped off. The committee divided these goods among the hospitals. Mr Eustace Illingworth donated a motor launch, allowing severely wounded soldiers at the Joint Hospital to enjoy the water whilst the more able men were able to take to row boats which were purchased for them.

It was ensured that the men, when well enough had plenty to keep themselves busy. The resident Chaplain, Rev. H. J. Peck, alongside the Cosy Corner Cinema arranged a film screening every fortnight, and the Hippodrome theatre arranged weekly dramatic performances. There were also a whole host of activities and classes that the men could take part in including bookbinding, embroidery and crochet, billiards and wood carving under the supervision of local sculptor Alex Smith. Many gifts were also donated by various individuals, including pianos, gramophones, seating, clocks, games, cigarettes and sterilising instruments.

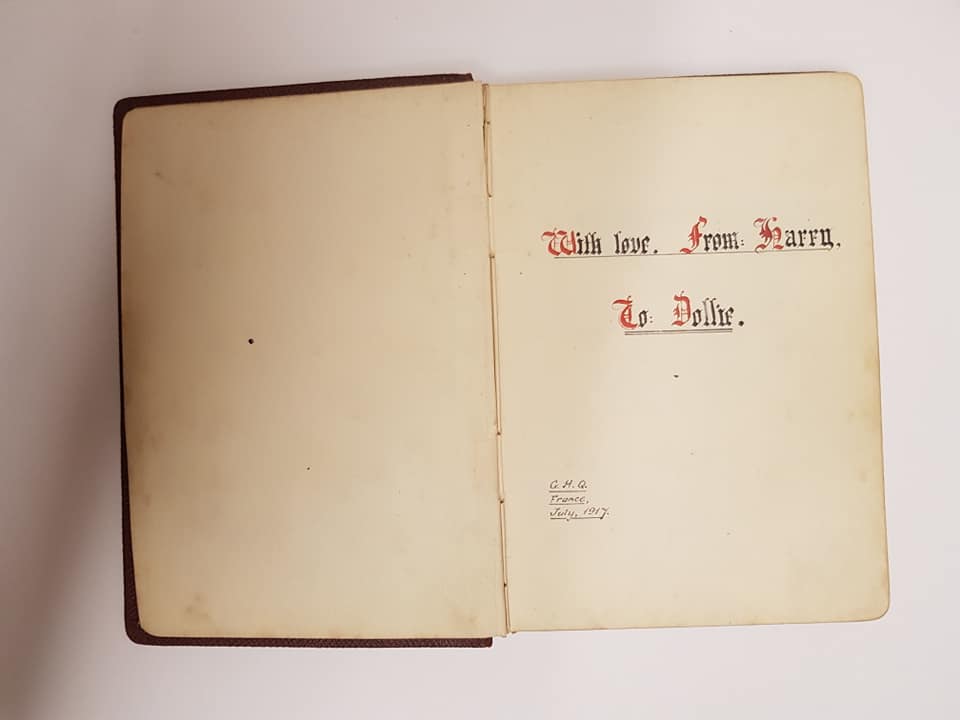

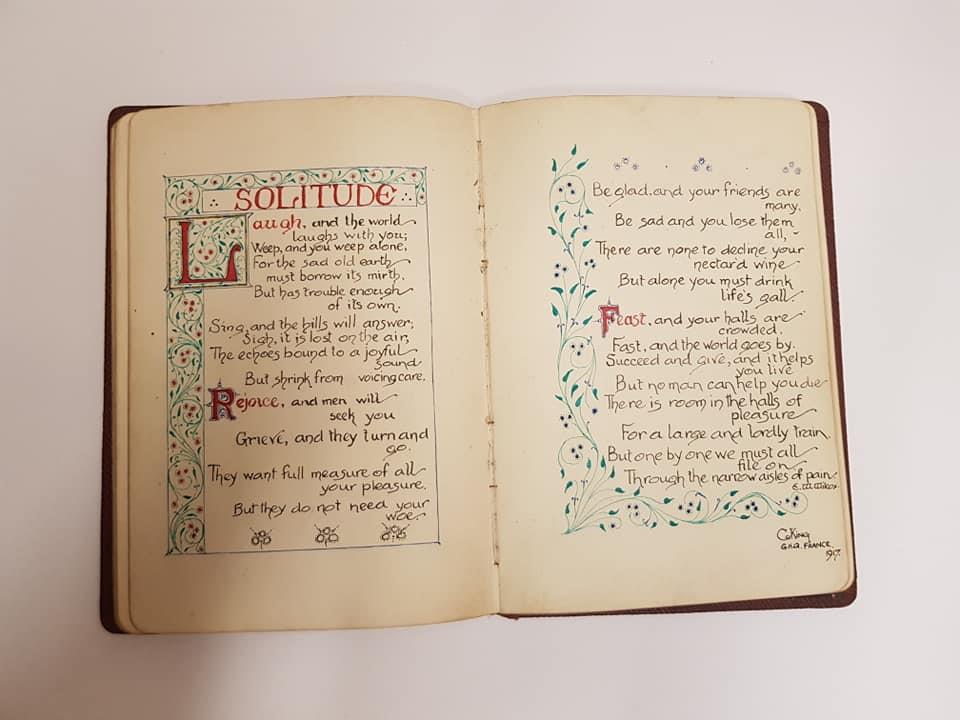

Another intriguing object from our collections is an autograph book. On closer inspection we discovered that the book was filled during a soldier’s time recuperating at the War Hospital. The book contains a variety of drawings and poems and illustrations, ranging from the jovial to the thoughtful, which were contributed by other convalescing soldiers and a series of women who could have been nurses or some of the aforementioned volunteers.

Many of the soldiers have written their regiment under their names, allowing us to see the mix of men who were brought here. The message at the beginning of the book From Harry to Dollie indicates that this book was probably intended as a gift to the soldier’s girlfriend, wife or sister. This identity of the soldier who owned the book again remains a mystery to us. There are comprehensive lists of the patients admitted to the hospital but they are listed by surname, something that we do not have here.

As the signatures of the soldiers’ in the autograph book suggests the hospital did not just cater for local men, but for men whose homes were spread across the country. This made it very difficult for many relatives to visit. To help solve this problem a charity cricket match was organised, raising funds to help with travel expenses. Arrangements were also made amongst local residents to accommodate the visiting relatives of the wounded.

On the 3 June 1919 the final patients were transferred to Huddersfield and the War Hospital closed its doors.

A rather poetic comment was made by Surgeon-General Bedford when reflecting on the soldiers’ situation and the hospital’s location, he said:

They knew that to some it would be the valley of the shadow of death, but to some it would be the valley of hope and healing.

Thanks to the over all care and compassion of both staff and volunteers the War Hospital and its auxiliaries treated 13,214 wounded service men, providing them with a degree of both hope and healing.