In this blog, Assistant Curator of Collections Dr Lauren Padgett shares her investigation into a collections conundrum regarding a 19th century shawl and uncovers how it is linked to a riotous week in Bradford and the surrounding area 180 years ago.

Collections Conundrum

A few years ago, a particular record on our collections database caught my attention. It was for a shawl described as:

Kashmir shawl of fine twilled wool, probably cashmere; Background is natural colour, borders and centre with coloured design, predominantly in reds and blues, worked in wools and silks; borders are probably woven, parts of centre embroidered; borders are of geometrical designs and vases of flowers, above which are shown figures in procession with elephants etc; centre panel is again geometrical; silk fringe along two sides of the shawl.

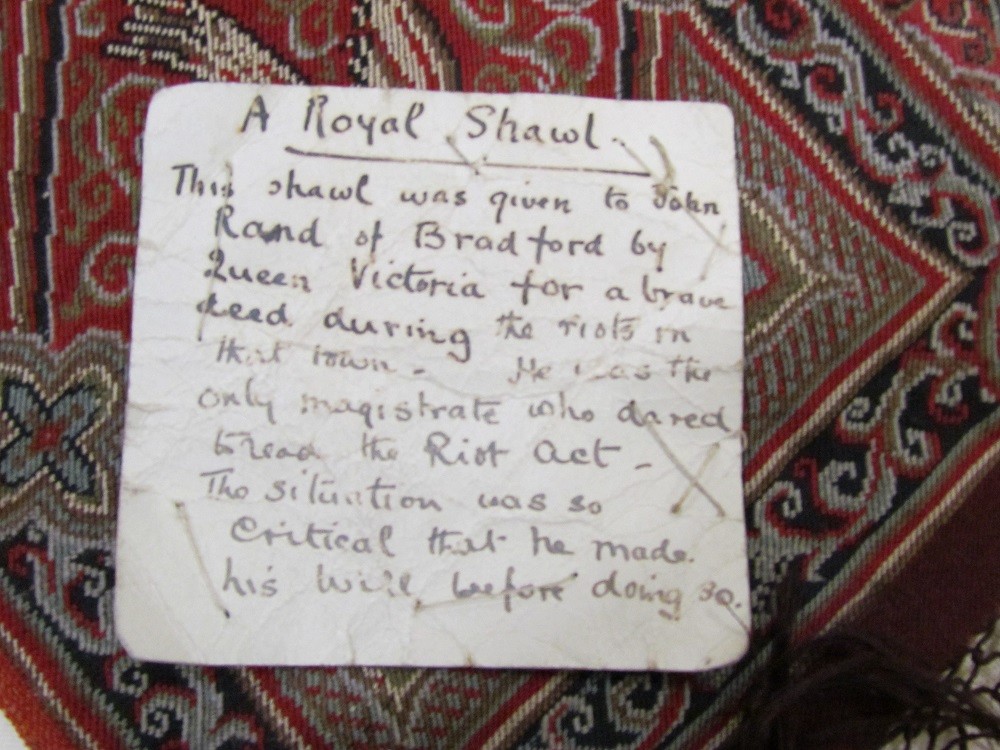

There are three photographs attached to the record. One shows the shawl laid out; another is a close-up of an elephant walking towards one corner; and the third shows a label sewn onto the back of it. It is handwritten with the title ‘A Royal Shawl’ underlined for emphasis with three sentences underneath:

This shawl was given to John Rand of Bradford by Queen Victoria for a brave deed during the riots in that town – He was the only magistrate who dared to read the Riot Act – The situation was so critical that he made his will before doing so.

Those three tantalising sentences paint a vivid picture. John Rand, a courageous hero who put himself in grave danger against rioting Bradfordians and was rewarded for his bravery by Queen Victoria with this royal gift. A plot like that would make a great period novel or film!

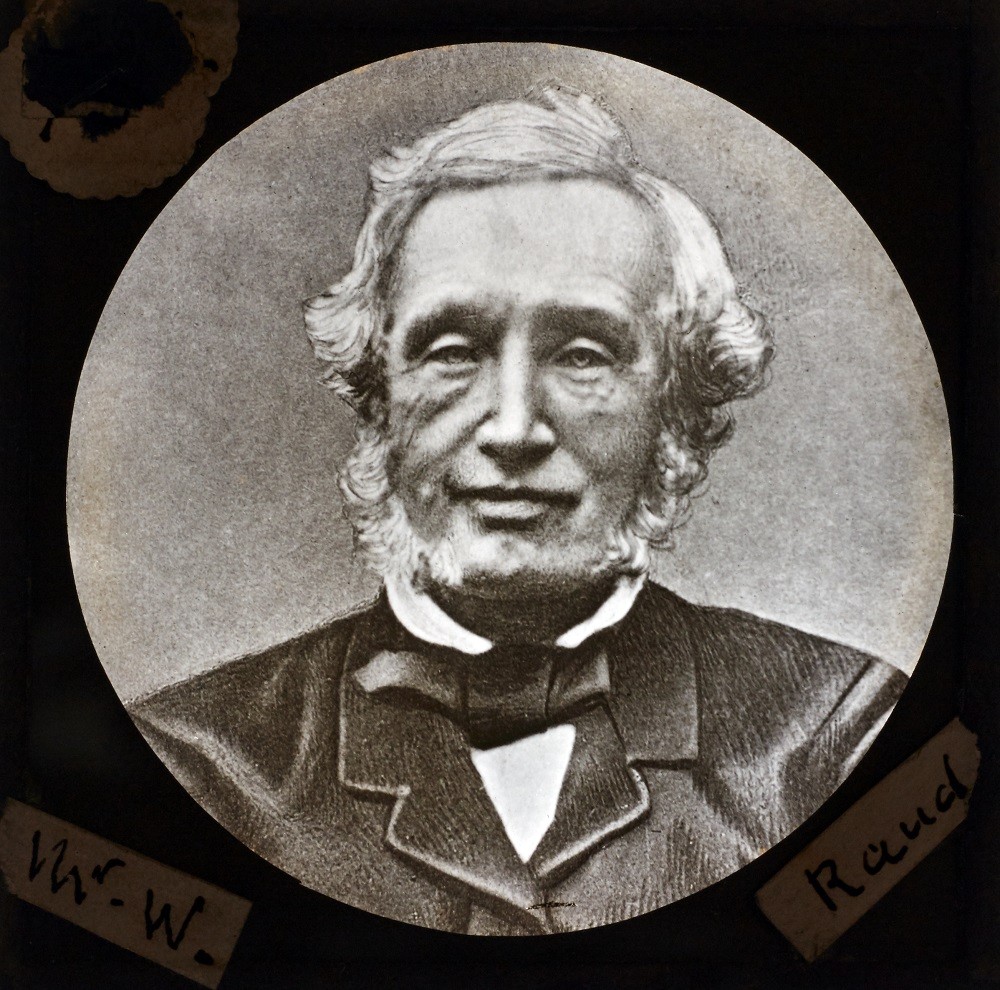

I scrolled further down the record. A note by a former curator reiterated what is written on the label but suggested it is ‘apocryphal’ (dubious) as their own research found that John Rand was not a magistrate – although research had evidenced that his brother, William, was Mayor of Bradford in 1851. Another note added under that by a more recent former curator says that they do not agree as their research found John Rand listed as a magistrate in 1845. I give the first curator – who may have been conducting this research back in the late 1960s (when the shawl was acquired) – the benefit of the doubt as the more recent curator had access to digitised documents for their research. This curatorial conundrum posed several questions: who was John Rand? Which Bradford ‘riots’? Is it possible that Queen Victoria gifted him this shawl? This year, I finally set out to do some research of my own.

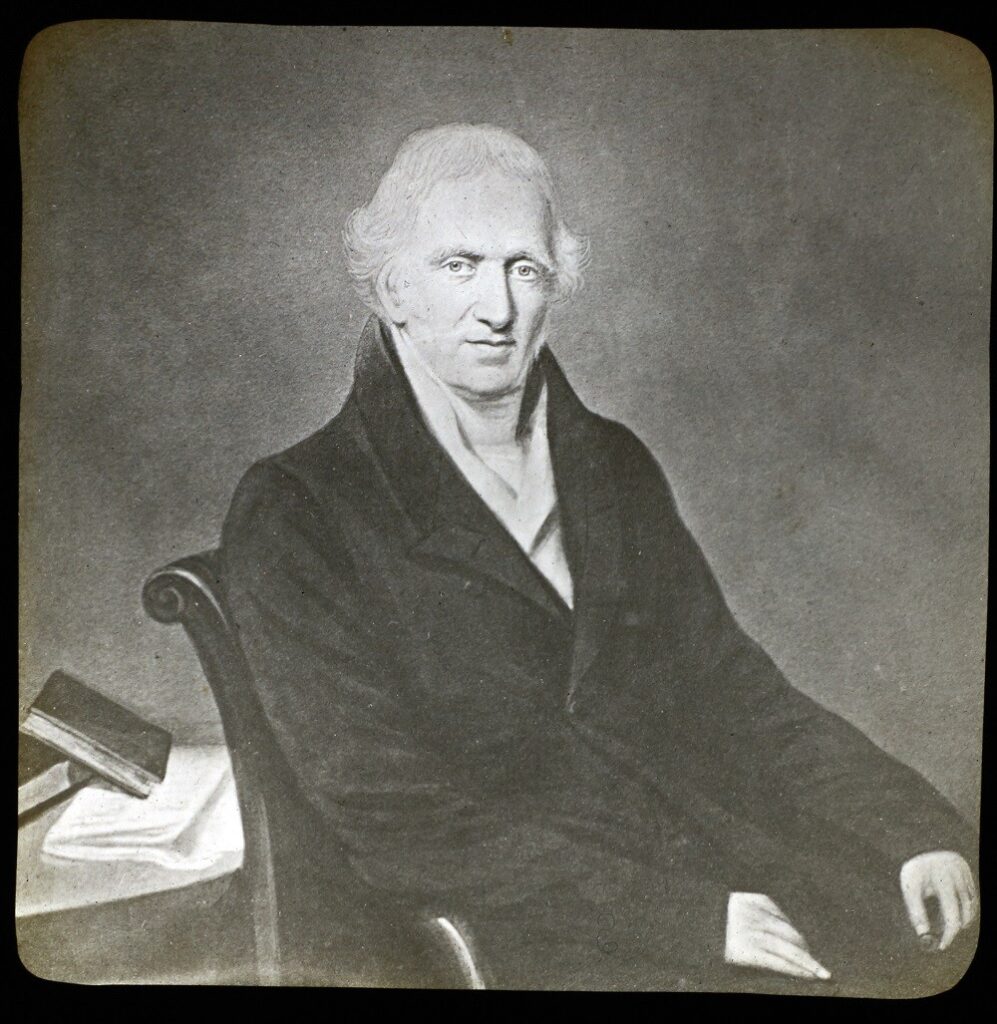

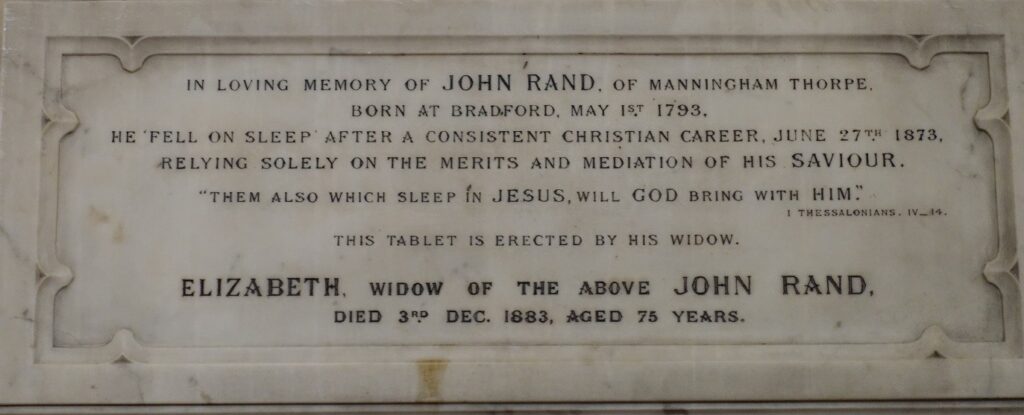

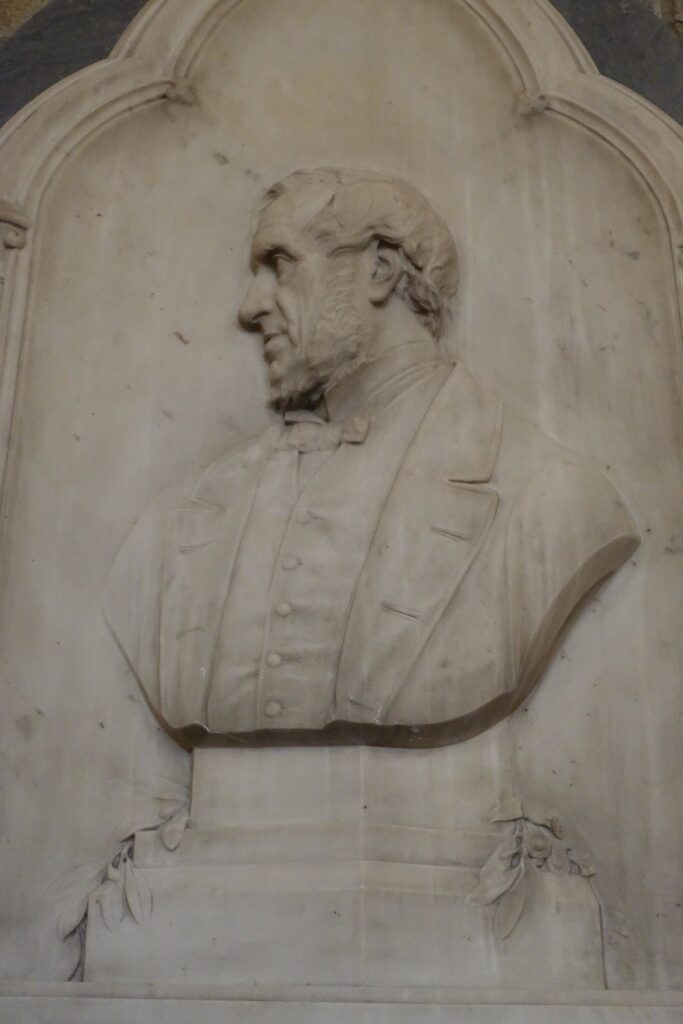

John Rand II (1793 – 1873)

John Rand was born in 1793 and died in 1873, aged 80. There is a memorial for him in Bradford Cathedral. He was in fact John Rand Junior. His father John Rand Senior, who had moved from Norfolk, established a successful worsted spinning mill in Bradford in 1803, alleged to have been the third steam-operated spinning mill in Bradford. The mill and company John Rand & Sons was later taken over by John Rand Junior and his brother William. I too confirmed that his brother William was Mayor of Bradford in 1850-1 and that John Rand Junior was a Bradford magistrate, for a few years in the 1840s at least. He had a ‘villa’ called Manningham Thorpe built on Toller Lane in the 1850s where he lived for many years – it still exists today as the former Lilycroft Working Men’s Club and presently as a restaurant. He was listed as a Guardian of the Bradford Poor Law Union in 1856, and was a founding member of Bradford Philosophical Society. As an ardent philanthropist, he had high quality working-class housing built in Little Horton and alms-houses erected at the bottom of his garden.

‘I predict a riot’

Having confirmed that John Rand existed, I turned my attention to disturbances in 19th-century Bradford. If I could pinpoint specific occasions when the Riot Act was read in Bradford, then maybe I’d find a reference to him. The Riot Act (1714) was a law which authorities could use to declare a gathering of twelve or more people to be unlawful/seditious and demand their dispersal. The punishment for not obeying the reading of the Riot Act was originally death, later reduced to transportation in 1837. The Riot Act had to be read precise and aloud to the crowd by a ‘head officer’, such as a Justice of the Peace, magistrate, mayor or sheriff depending on whether the area was a town or village. There was a lot to riot about in the 19th century. The early part of the century in particular was full reasons for discontent that could have resulted in public disturbances or organised rioting, like the Chartist riots.

Chartism was a political movement which was founded in 1836 and peaked from 1838 to 1848 during a time of particular economic depression and poverty. Working-class support for Chartism was fuelled by resentment towards the Corn Laws. The Corn Laws, introduced in 1815, were tariffs and trade restrictions which benefitted domestic producers by blocking cheap imports of corn and other foods. This inflated the cost of living, increasing the price of food at times of shortages, making the lower classes hungrier and the wealthy producers wealthier. Chartists wanted to introduce a People’s Charter of six key reforms to reform the electoral system and increase working-class political participation, in the hope that they could then repeal the Corn Laws, amongst other things. In June and August 1842, the North of England was particularly suffering from famine and high levels of unemployment so feelings of discontent were running high. Support for the Chartist movement therefore grew and some mass meetings turned into raucous riots in Yorkshire towns like Halifax and, significantly for us and John Rand, Bradford and Cleckheaton.

This is the political, social and economic backdrop to the riots that John Rand faced. Piercing information together from different sources has confirmed that John Rand had faced rebellious rioters twice in one week 180 years ago in 1842.

Sunday

On Sunday 14th August 1842, a Chartist meeting was held at Bradford Moor, Bradford, where, it was reported, 10–15,000 people assembled to hear speakers who proposed that labour should be withdrawn (mass strike action) until the Chartist’s People’s Charter was introduced. “We are determined” they cried. Meantime a different meeting took place across town in Talbot Inn. Concerned local magistrates and constables had organised their own meeting to take “precautionary measures to preserve the peace of the town” by swearing in special constables and requesting troops from the 17th Lancers Yorkshire Hussars Regiment to be sent from Leeds.

Monday

On the morning of Monday 15th August, a public meeting was held opposite Odd Fellow’s Hall on Thornton Road, Bradford. Speeches covered a wide range of issues from lack of working class representation in the House of Commons to the failings of the New Poor Law (which made conditions worse for the most vulnerable in society), whilst championing the People’s Charter and encouraging organised mass strikes. “Will you follow us?” the speakers asked the crowd, “We will” was the reply. The speakers declared “Now let every one who is resolved to abide the consequence, fall peaceably into rank and follow us” and led a crowd of men and women, of which reports vary from 5–6,000 and 8-10,000 in number, up Manchester Road. Troops of the 17th Lancers, ordered by local magistrates, followed the crowd as they stopped at mills along the way demanding “the turn out of the hands” (workers) who joined them. The growing crowd continued to Halifax to meet up with a large group of Chartist supporters from Lancashire, forming a crowd of 25,000. In Halifax, the crowd relieved mills of workers, damaged mill boilers and emptied mill reservoirs, which closed mills down. Troops arrived, the Riot Act was read and arrests made. After some individuals were arrested, there was a violent confrontation between the crowd and troops that resulted in missiles being thrown, shots being fired and a sabre charge. It was anticipated that this type of rioting could spread across neighbouring towns. However, luckily for Bradford, its supporters returned from Halifax to their homes peaceably – for now. The empting of mill ponds, dams and reservoirs and the unplugging of steam engine boilers which incapacitated the mills resulted in these riots being known as the ‘Plug Plot’ Riots.

Tuesday

On the morning of Tuesday 16th August, a meeting was held again on Thornton Road, Bradford, but this was merely a meeting point as the crowd marched to Listers’ Mill at Manningham, Mr Hargraves’s Mill at Frizinghall and others in Shipley. At each mill, they successfully demanded that the ‘hands’ (workers) joined them resulting in the closure of the mills. They planned on passing through Bingley and Keighley. Meanwhile, another group remained in Bradford and grew in size. They went to Rand’s Mill and attempted to let the water out of the mill’s dam. William Rand is reported to have gathered a band of workers, armed with “pitch forks and bludgeons”, and confronted the crowd only to be “met with a volley of stones which caused Mr. R. to retreat – to run – in which he was followed by all his party”. It is probably no surprise that at this point, the local magistrate John Rand and the 17th Lancers troops swiftly responded. The Riot Act read and the crowd was ordered to disperse, resulting in “shouts, hootings, and groans” before they destroyed the mill pump and proceeded onto another mills. While successful at ‘turning out hands’ and closing some mills, they failed at a couple which were defended by the troops and the disappointed crowd slowly dispersed. By four o’clock, it was reported to be “quiet as a calm a before a storm”, but the storm would occur elsewhere.

Thursday

On Thursday 18th August*, a crowd of Chartists had gathered in Birstall and after speeches, a procession set off to Cleckheaton. Aware of the approaching danger, local Mr. James Anderton rode to Bradford in an impressive half an hour for reinforcements to defend Cleckheaton, while locals and special constables steadied themselves. The crowd of 5-6,000 men “armed with formidable bludgeons, flails, pitchforks and pikes” arrived in Cleckheaton, attacking and ‘unplugging’ the first mill. Then they went to St. Peg Mill and had “withdrawn the plugs from two of the boilers” when they were disturbed by the arrival of soldiers. Cleckheaton’s special constables had joined forced with the just-arrived Yorkshire Hussar troops from Leeds and a “little band of horsemen, led by … Mr. John Rand, of Bradford”. John Rand, whose pride may still have been bruised from the attack on his own mill a few days earlier, addressed the crowd appealing for peace. Before the Riot Act could be read, the crowd threw missiles at the magistrate and troops. An order was given for the troops to fire into the air above the crowd, twice, causing the crowd to retreat into the nearby beck and fields. The troops charged forward striking people with the flat sides of their sabres. As the crowd dispersed, the special constables armed with truncheons stepped forward taking some prisoners.

So there we have it: the story of Bradford’s John Rand and how he faced rioters twice in as many days. Frustratingly, I haven’t come across any evidence yet that Queen Victoria presented him with the shawl. But on the shawl’s record, underneath the other curators’ notes, I have now added my own note with a summary of this research, satisfied with what I have uncovered after it has been shrouded in mystery for so long.

*There seems to be a discrepancy as to when the Cleckheaton Plug Riot occurred. Some sources say the Thursday of that week (18th August), but some other sources say it occurred on the 17th which would make it the Wednesday. I’ve gone with Thursday 18th.

Sources

‘Alarming Riots in the West Riding of Yorkshire’, Bradford Observer, Thursday 18 August 1842, p.6.

‘The Disturbed Districts’, York Herald, Saturday 20 August 1842.

‘Bradford’, Yorkshire Gazette, Saturday 20 August 1842, p.8.

Frank Peel, The Risings of the Luddites, Chartists and Plug-Drawers, 1880.

Frank Peel, Spen Valley, Past and Present, 1893

4 Responses

On the confused motivations of The Chartists, I wonder what the Assistant Curator’s take on a certain Mr George White would be. For he was a Chartist who aspired to office in Bradford as a Tory(!) councillor. Now as Chartism was a reaction by the ‘working’ man against those that had achieved particularly good fortune in business i.e. the unscrupulous mill owner and business man (but ultimately as a derivation from the dissatisfied wool comber turned wool stapler). Was Mr White trying to express dissatisfaction at the rise to ascendancy of the ‘working’ man, competing with the interests of the old money, the landed aristocracy (The Tory’s) in both business and agricultural production – in that they were now aspiring to reverse The Corn Laws and the monopolies the landed gentry had on food, or to threaten them by acquiring the vote, or simply by becoming wealthy in an age with no welfare (the new poor laws even not being to the ‘working’ man’s taste).

oh my goodness! You have answered a question for me. I have exactly that shawl. It has been a mystery which now is partly solved! I bought it from a second hand shop while on holiday in New Zealand in 2025.It would be wonderful if you have any other information regarding the shawl. It was obviously produced en mass but by whom and where would be exciting to know. By the way I live in Victoria, Australia on a rural property and love my shawl. It hangs on a wall in pride of place.

sorry, the date was 2005 not 2025

Fascinating read! The history behind the royal shawl is so intriguing your post beautifully uncovers its mystery and cultural significance. Well done!