This week’s blog has been written by Antonia Lovelace, Curator of World Cultures, from Leeds Museums and Galleries.

This year we have the promise of three days partnership work by Antonia, as we try to assess the breadth and quality of world culture representation in our collections, as part of an on-going collections review. The East Asian collections, from China and Japan, already stand out in the Decorative Art displays, and the South Asian collections have been significantly developed with an emphasis on both Art and Decorative art, since the work on the Transcultural gallery began under Nima Poovaya-Smith in the 1980s, continuing under the guidance of Bradford’s Curator of International Art, Nilesh Mistry. But what about material from the Pacific, Africa, the Americas, and Europe, that used to be termed ‘Ethnography’?

Last month we began our review at Cliffe Castle.

The first object to wow Antonia was this ceremonial fish club from the Nootka people of British Columbia in Canada. Nootka is now spelt Nuu-chah-nulth and their tribal council is on-line here. A researcher in the 1980s, Alan Hoover from the Provincial Museum of British Columbia, had identified the item for us. The main body of the club features a man or person holding a whale to their stomach, their hands touching just under the whale’s head. On the reverse a large hand reaches up to cover the top of the man’s head. Below the narrower grip section is a second smaller person’s head.

Looking at the collections web-sites of the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia (MOA), and the Royal Museum of British Columbia you can see a wide range of different hunting and ceremonial clubs from the Northwest Coast area, of wood and bone, some plain, some carved and some painted. It seems that the clubs are named after the sort of animals depicted and that clubs with fish on are called fish clubs, clubs with otters on otter clubs and so on. Take a look at MOA’s collection online using the keyword Noota+Club and then admire the display of amazing totem poles in the gallery at the Royal Museum.

Northwest Coast cultures are famous for their depiction of sacred totem animals in their art, both on the huge totem poles, and on smaller items like the ceremonial fish club here. The large hand reaching over the back of the head is also a common design feature on Nootka clubs, though often the ‘head’ is just a sphere. One wooden club of this plainer type, originally collected by Captain Cook, was in the news in 2012, when an American collector sold it to MOA. Go to The Globe and Mail article for more information.

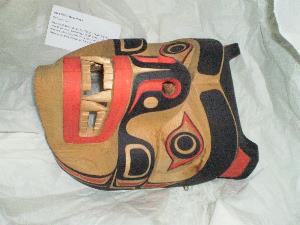

The earlier research believed the Bradford Nootka fish club to be over 100 years old. Amongst our Canadian collections it is now complimented by two modern masks by Richard Hunt acquired in 1981, a portrait mask, with a beak like nose, and a bear mask.

It seems that these North American collections, which also include Inuit and Plains material, have attracted regular attention in the past, as their records are generally better kept, with more researchers’ comments.

Leeds Museums and Galleries recently had a visit from the British Museum Australian specialist Gaye Sculthorpe, who is undertaking a review of Australian Aborigine collections in the UK, so Antonia also picked out two Aborigine baskets or dilly bags as remarkable for their quality and colour. These long tubular baskets are made from weaves of plant fibre woven round narrow splints. Red ochre and white lime paint has been applied over the natural yellowish colour of the splints or a yellow ground to create subtle geometric designs. The smaller basket has a more open weave with white dots either side of vertical red bars. In the longer basket narrow white stripes divide the red into regular horizontal bands. Each has over-stitching of darker plant fibre at the rim, with a multi-strand carry-handle of the same fibre surviving more completely on the larger basket. Both baskets were acquired in 1915 and are in remarkable condition. After we have examined the rest of the Australian collections at Bradford we plan to write a report for Gaye Sculthorpe and get her comments on the material.

Using the British Museum collections search on-line we can see that the designs on these two baskets are pretty basic compared to several more elaborate ones from Port Essington in the Northern Territory. Look up basket Oc.1939,08.37 for example In ‘Curator’s comments’ is a note: Baskets were, and still are, made in this region by both men and women. They are often painted, and ancestral knowledge is passed on through the designs and through the significance of the colours used.

If you did not catch the amazing ‘Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation’ exhibition at the British Museum in London in 2015 you can still get hold of the catalogue, published by British Museum Press, and feast your eyes on both ancient and modern Australian art forms.

Lastly we want to share with you a vibrant folk art painting from Odisha state in India (formerly known as Orissa). It’s just a small rough circle, about 10cms wide, with two large eyed schematic deity figures separated by a tinier one in the middle. The orange background, bright colours, and contrasting white and black Hindu deity faces, immediately demand attention. They are in the distinctive style of Patta-chitri painting from Odisha or Orissa. The deities shown are Lord Jaganath, an incarnation of Lord Krishna, and Lord Balabhadra and Maa Subhadra, Krishna’s his younger sister who is the tiny figure in the middle.

Go to this essay by Akanksha Pareek and Prof Suman Pant currently available as a pdf on-line if you want to know more.

Turning the painting over to check for an accession or record number we found the name of the donor, John Brigg, and a 1925 date, so this small painting has survived really well.