Last year, one of our followers, Sally contacted us to see if we would be interested in a blog written about an interesting local (and not-so-local) story that would be relevant during Black History Month.

She writes:

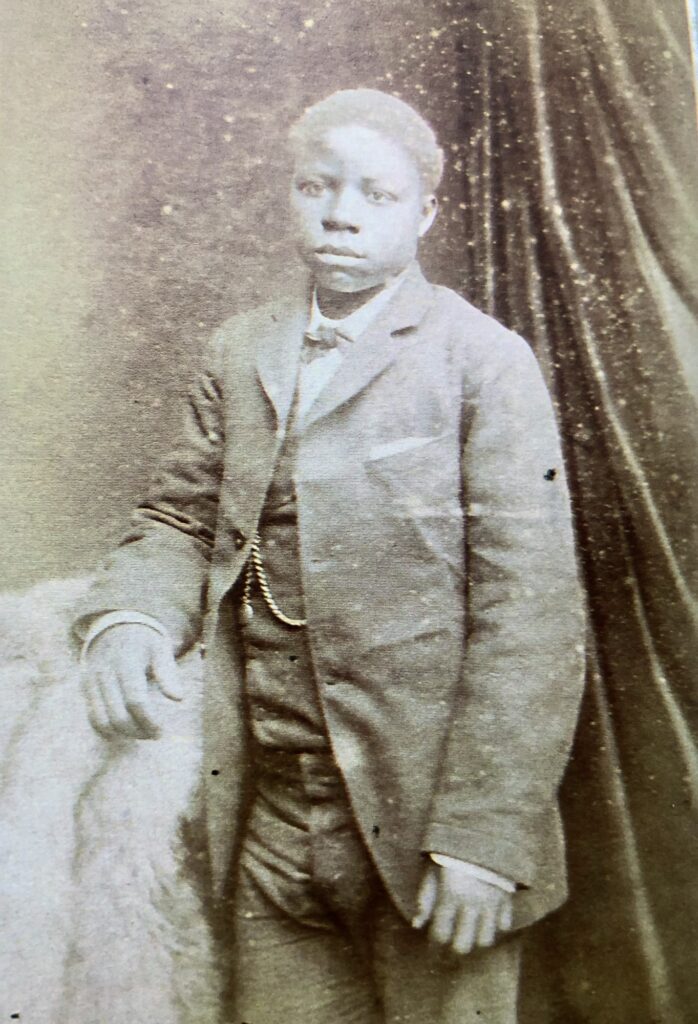

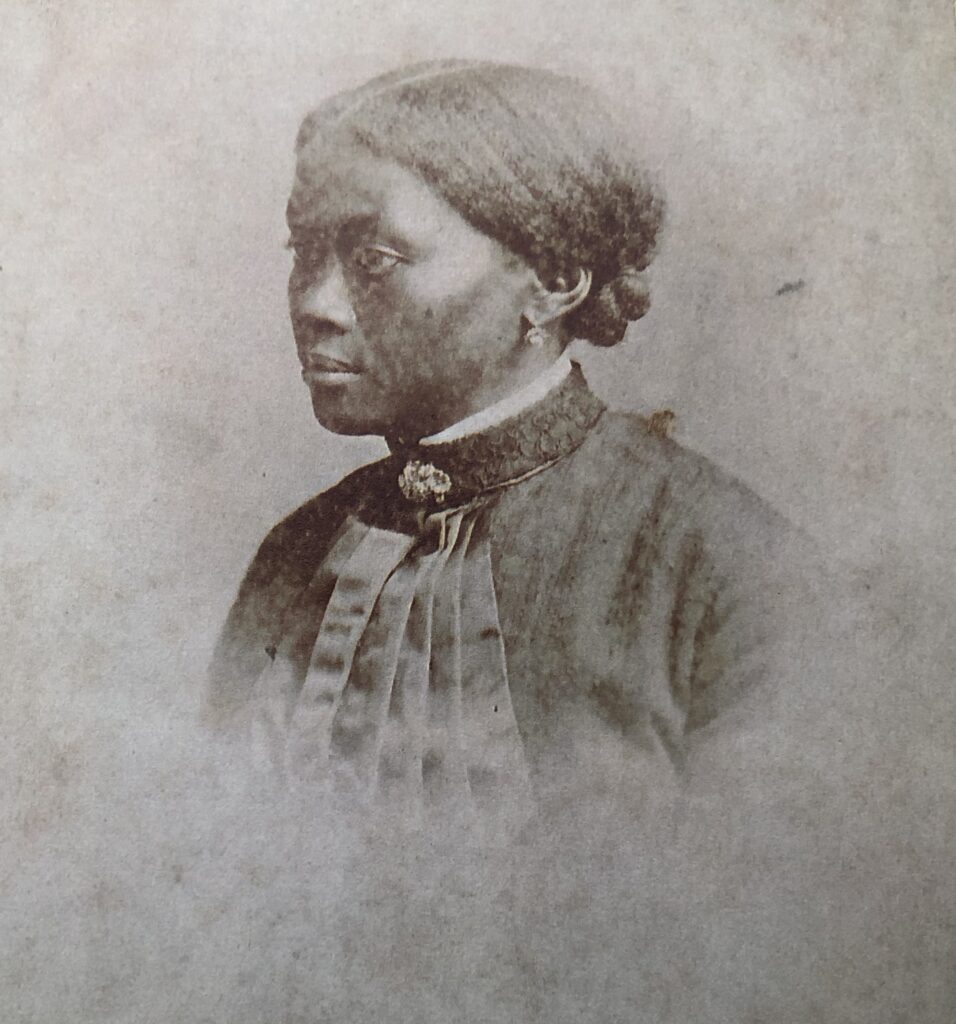

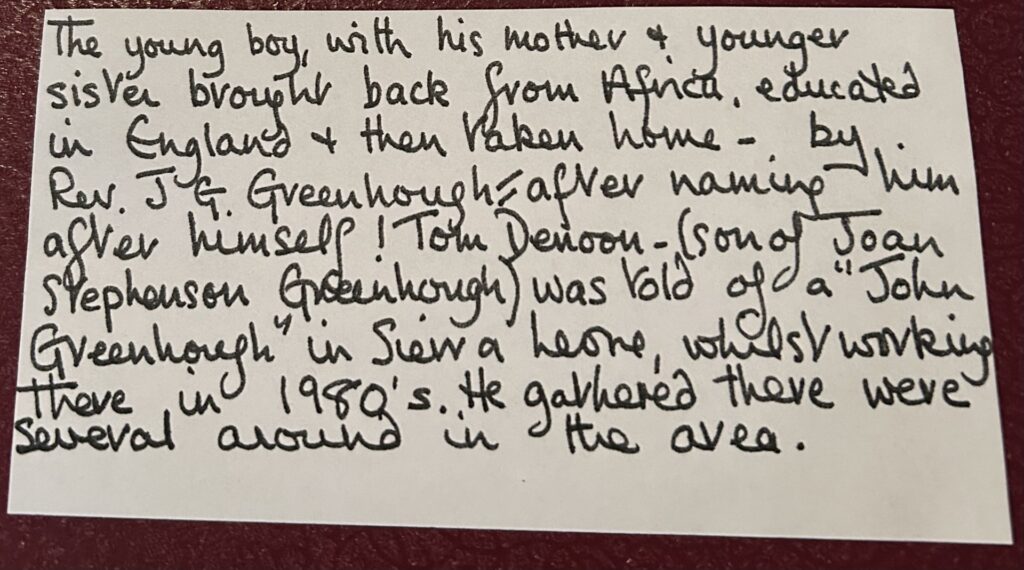

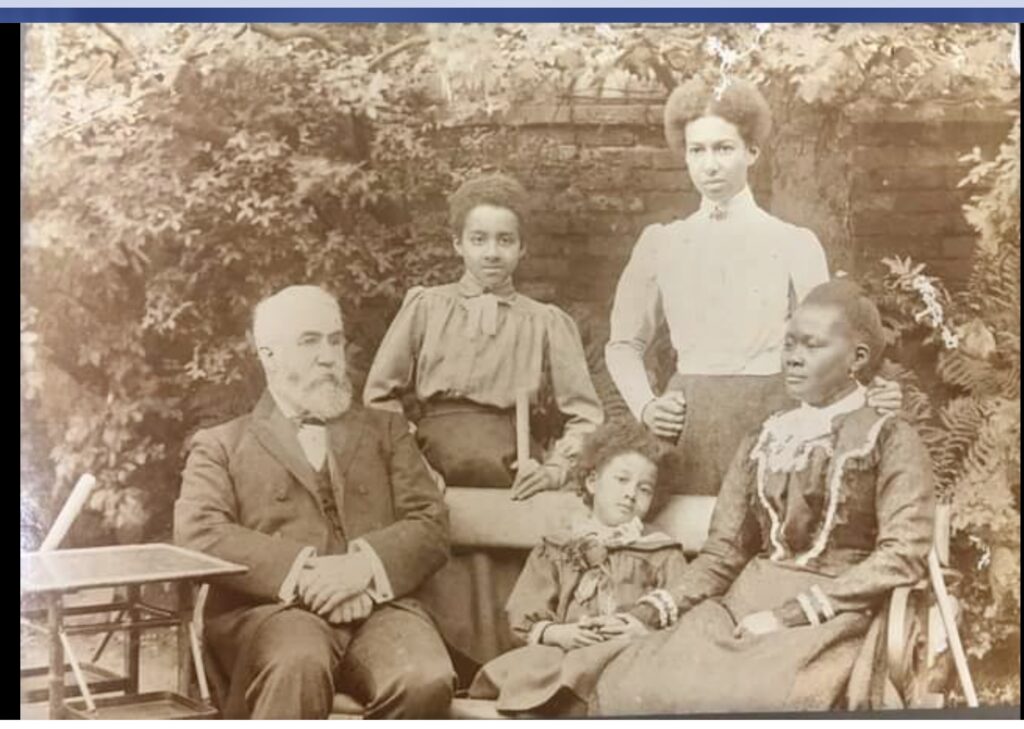

Some years ago, I inherited three Victorian photographs taken in England of people of African heritage.

In the final months of her life, my mother had sorted generations of old family photographs and letters into bundles to be left to each of her children. Amongst mine were those three photographs. They showed a boy who had been named after my great-great-grandfather, the Reverend John Gershom Greenhough, and a lady and a young girl whose names were unknown.

Accompanying the photographs was an intriguing note from my mother that hinted at hidden histories and a possible family connection to Africa.

Fascinated, I tried to find out more, but made little progress – until I chanced upon a recently written book describing a financial dispute involving “….a curious episode concerning one John Greenhough, or rather two John Greenhough’s [sic]” 1

This text gave me the connection between my ancestor, Rev. John Greenhough, the younger but unrelated John Greenhough in the photograph, and the 19th-century missionary George Grenfell, who was closely tied to the two men.

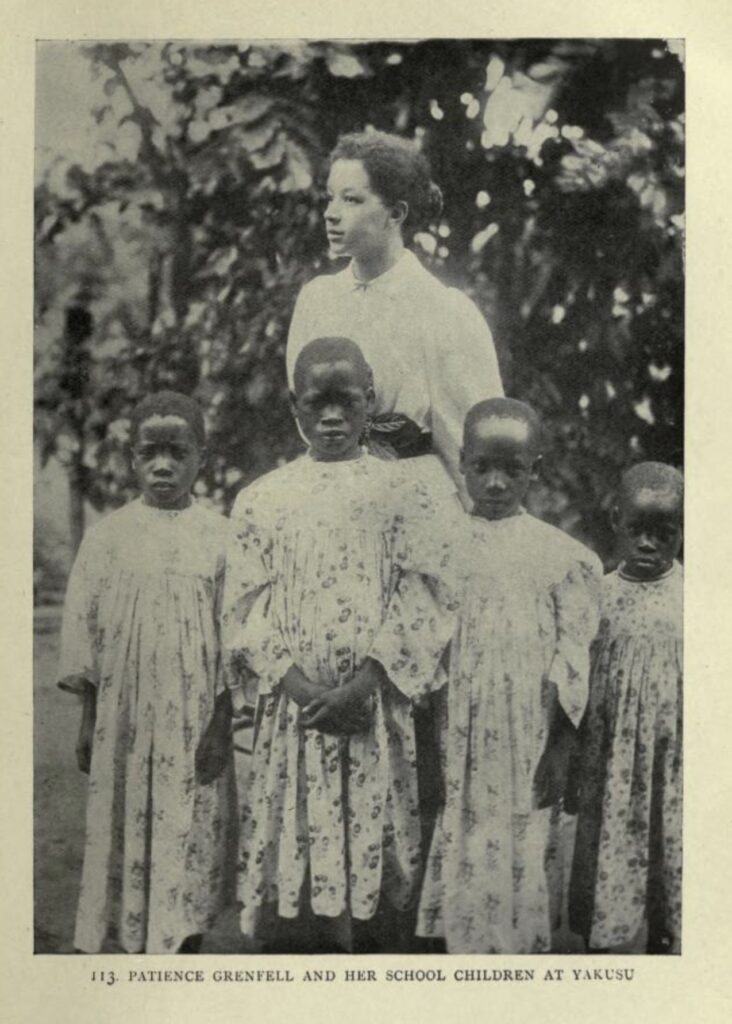

I now had names for all three people in my photos: John Greenhough, Rosana Grenfell (George’s wife), and one of the Grenfells’ children – probably Patience Grenfell.

From here, I was able to research their stories – and their connections to Yorkshire.

Colonialism and the Work of the Missionaries, 1850s-1910

A little background of the era

This story is set in what is known as the age of “New Imperialism” when the major European countries “scrambled for Africa”, claiming land and control. England had abolished slavery in 1833 but dealing with the aftermath wasn’t straightforward.

The work of missionaries like George Grenfell in Africa and elsewhere, is now seen more critically than it was at the time, but they were well-intentioned.

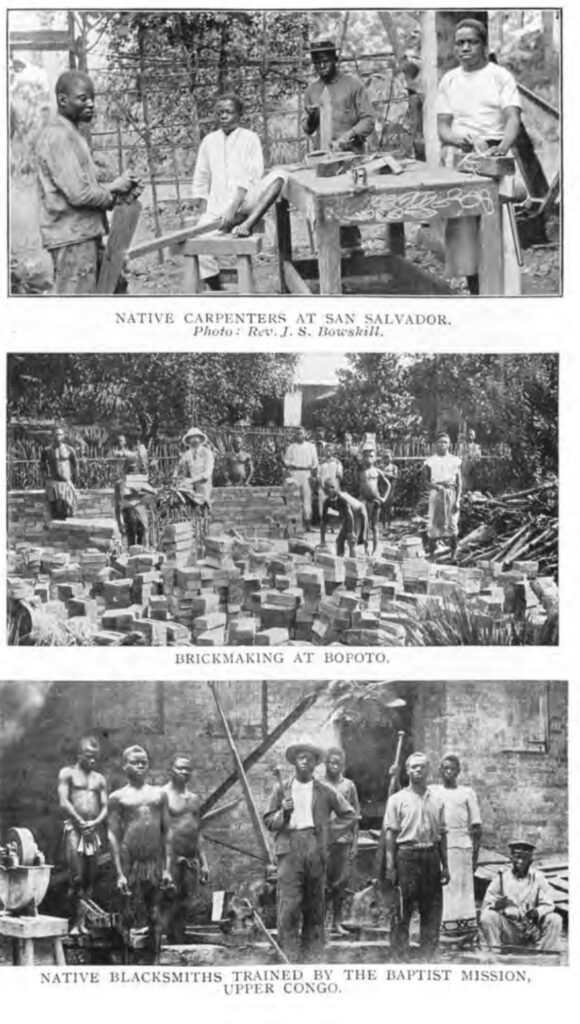

Missionaries mapped unexplored areas, built schools, taught skills, trained doctors and improved infrastructure – all financed by benefactors in England who were motivated by their religious convictions and a wish to improve conditions and “civilize”. However, the concept of imperialism was rarely questioned.

The Congo of the 19th century where Grenfell did much of his work was personally controlled by King Leopold II of Belgium.

The King had charmed most of Europe with promises that everything he would do there was for the benefit of the African people. However, over the years evidence emerged of the King amassing great wealth from the country’s resources using forced labour and atrocities carried out against the native Africans, particularly in the rubber trade.

Rosana (Rose) Grenfell

The woman in my mother’s set of photos was Rosana Patience Grenfell, known as Rose.

Rose’s family are said to have originated from Jamaica. Most probably her grandparents travelled to West Africa in the 1830s along with other previously enslaved Jamaicans to work as missionaries. These Jamaicans, amongst the first freed people set up a mission on the island of Fernando Po (now Bioko), which was used as a British anti-slavery post off West Africa.

The Jamaican and British missionaries worked together here to help displaced people wanting to return to Africa after the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Along with the intention of spreading Christianity, people were rehomed, educated and taught skills at these missions.

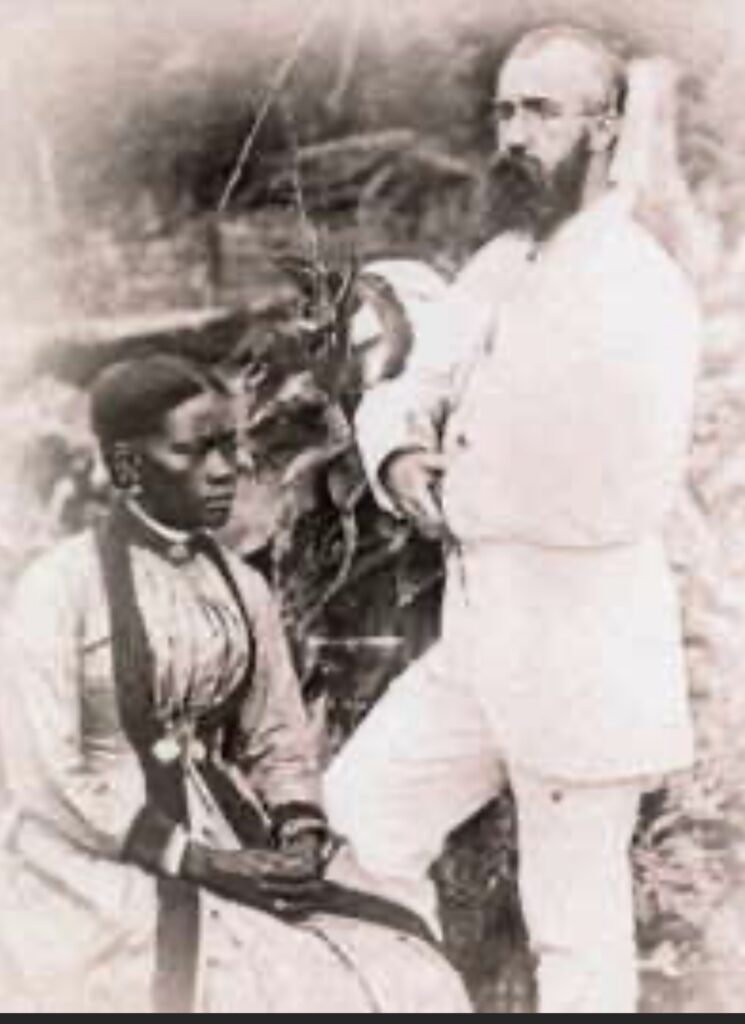

Rose was housekeeper to the Baptist missionary Reverend George Grenfell in the Victoria, Cameroon station. Grenfell was a prominent figure in his time. He was a determined missionary, working most of his life in Africa in Cameroon and the Congo.

Grenfell’s wife Mary died shortly after arriving at the mission. Africa was dangerous for British missionaries and adventurers. Doctors had no antibiotics and their understanding of disease was only just progressing from the idea that it spread through the medium of “bad air” or miasma. Missionary work in Africa was termed “a shortcut to heaven”.

A relationship developed between Grenfell and Rose after his wife’s death. Grenfell resigned from his position in the church after the unmarried Rose became pregnant. His official biography, written by a friend, skirts around this period, stating that there was little work at the mission so Grenfell had left to take on local paid work 2 . There is no mention that he had in fact resigned after several missionaries had written to the secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society telling him of Grenfell’s behaviour.

After a two-year period in which George and Rose were married and their first child Patience was born, he was welcomed back as a missionary.

John Greenhough of Africa, formerly known as Ti

Earlier in his career in Africa, before he moved to the Congo, George Grenfell worked in a mission in Cameroon where he met John Greenhough/Ti. As a small child John was simply known as Ti. He was always at the mission and helped in the formalities at Christian services. Known in George Grenfell’s official biography as “Rose’s favourite boy in the village,” she was a motherly figure towards him.

My mother’s note left with the photographs suggested that Rose was John Greenhough/Ti’s mother. Whilst not impossible that Rose (who was around 24 years in age) had already had a young child before her relationship with George, I have not managed to find any historical evidence of this, so John remains “Rose’s favourite boy.”

George Grenfell decided that Ti was a “great boy” who deserved a “great name”. He therefore renamed him as John Greenhough, after his well-respected lecturer at his Baptist College, who also became John/Ti’s sponsor. (No doubt the renaming of Ti was intended to honour both parties, but would be less acceptable in postcolonial terms.)

Nonetheless, George, Rose and their young child settled into missionary life at the mission with young John Greenhough/Ti. There, he received an education and learnt trades that would influence his future and open him up to what would then have been incredible adventures and opportunities.

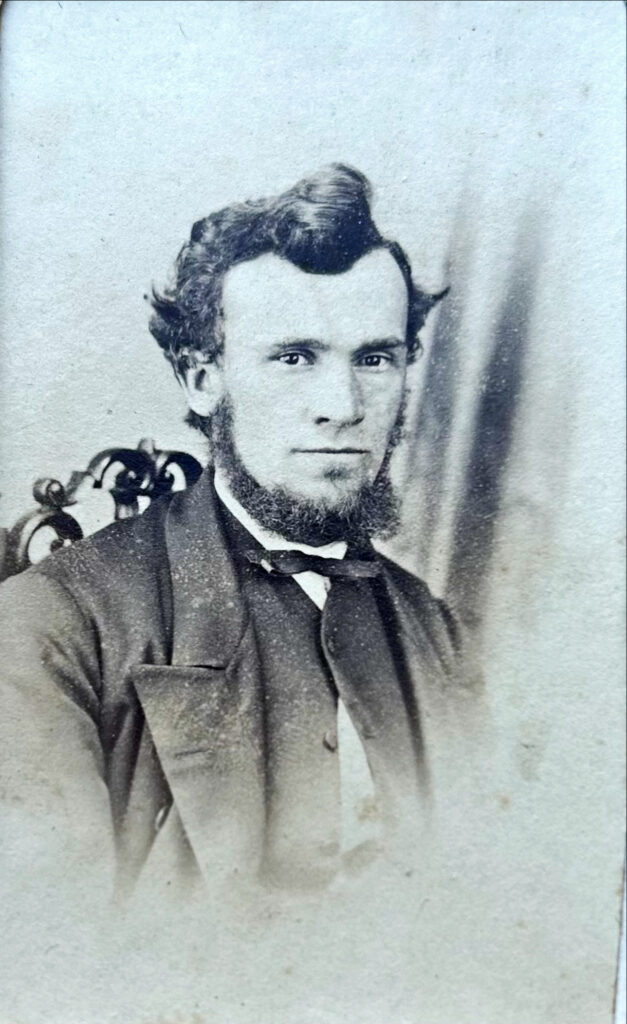

John/Ti’s namesake and Sponsor, Rev. John Gershom Greenhough

Our first Yorkshire connection, Rev. John Gershom Greenhough (my ancestor) had been a humorous, blunt and somewhat controversial young lecturer. He made a great impression on the young George Grenfell at Stokes Croft Baptist College in Bristol. Rev. Greenhough was clever and politically minded. An expert at Bradford Library Archives described him to me as a real character – in fact, a troublemaker. He was vocal during a split in the Baptist church at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and was part of a group that caused friction in politics, taking many non-conformist Christians from the Liberal party to what became the modern Conservative and Unionist party.

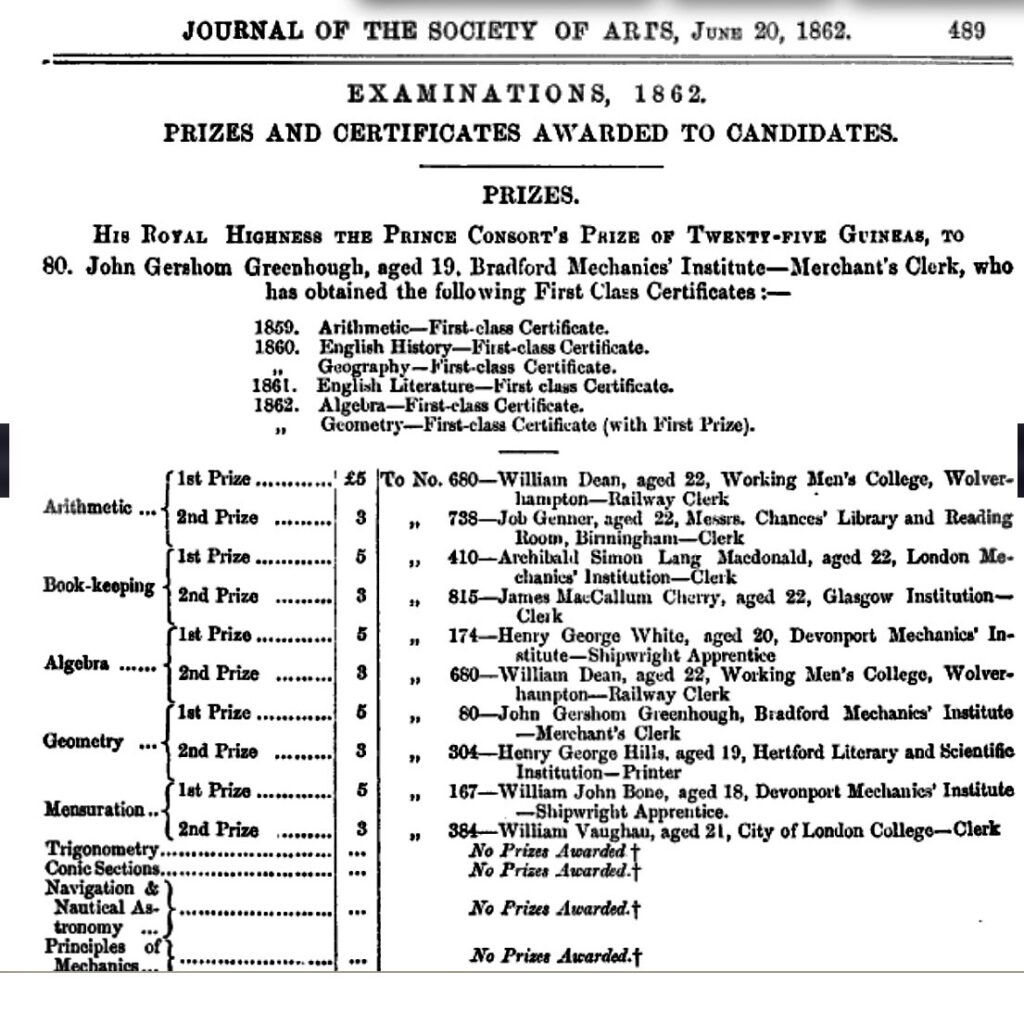

Brought up in Bradford from a working-class family, Greenhough left school aged eleven to work as an apprentice. He took evening classes at the Bradford Mechanics Institute and aged nineteen, he won the Prince Consort’s Prize for the best exam results in the country in his field. This led to a place on a scheme for bright but disadvantaged young people and then to a clerkship in London at the Privy Council3

In 1864, after two years in London, he returned to Bradford where he attended Rawdon Baptist College, gaining a degree in1866 and a masters in 1867. Now a minister, he was ready to leave Bradford with his new wife Sarah Stephenson, to lead his own church and teach in the Baptist College in Bristol.

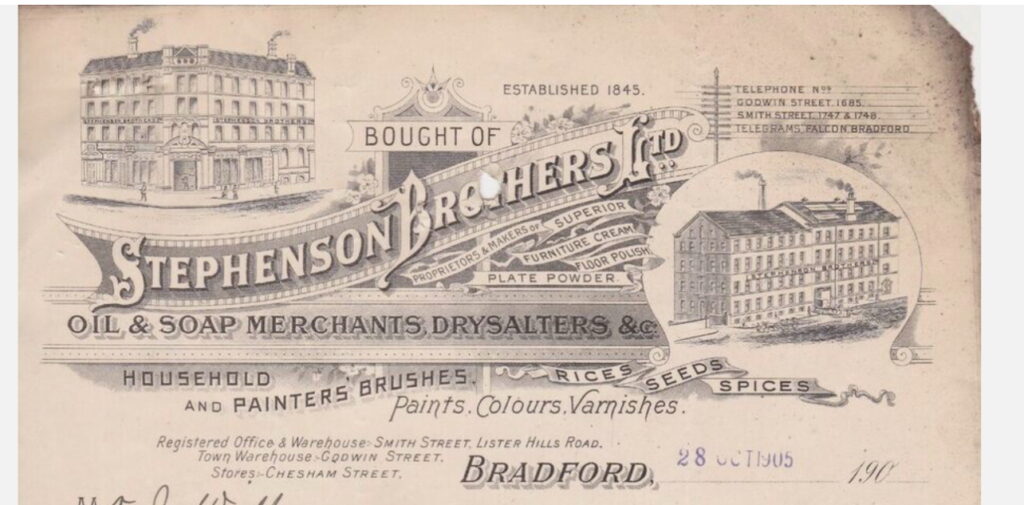

Meanwhile, Sarah was from a family of religious Bradford industrialists. The source of their immediate family wealth, Stephenson Brothers Ltd, was a business in manufacturing cleaning products. Today, there is large derelict mill still standing at Listerhills. Sarah’s financial interest in the company allowed a monthly income for the Greenhoughs which supplemented John’s income from the church and his writing.

Robert Arthington aka The Headingly Miser and Sponsor of the Congo Mission

Our second Yorkshire influence in this story is the incredibly wealthy but eccentric Robert Arthington from Leeds4 He funded the Congo Mission that changed the lives of the Grenfell family and John/Ti.

Although the most generous philanthropist of his time, he was said to have the appearance of “a tramp” and lived on a strict weekly budget of half a crown. Hence, he was known locally as the “Headingley Miser.” Living in a large house, he confined himself to one room where he slept in a chair with his coat for a blanket. On the rare occasions when he had a visitor, he refused to light a candle as he said, “You can just as easily talk in the dark!”

Arthington’s mission was to spread the gospel across the world. He funded scores of projects in countries including Africa, South America, China and India. His legacy to the Missionary Societies on his death in 1900 was a million pounds, which would be a value of around one hundred million pounds in 2025.

His “Congo Mission” would take Christianity across Central West Africa. He wanted George Grenfell to take command and Grenfell, who had found early inspiration in the explorer Dr Livingstone, was only too pleased to accept.

The Congo Mission and The Peace

Arthington started his Congo Mission by funding the building of a boat and the cost of a crew.

A small steamer to be named The Peace was built on the Thames in Chiswick. It was specially designed for the Congo river which, although huge and incredibly deep, also had many areas of shallow waters with hazardous rocks and sand banks. The boat was designed with a draught as little as twelve inches. It was modular in order to be disassembled and carried when they met cataracts in the river.

Once built it was displayed on the Thames under Westminster Bridge where it received a lot of interest, including visitors from Parliament and the press.

It was then dismantled, numbered and packed into 800 cases, each considered to be a weight an African porter would be capable of carrying. It was then transported to Liverpool and then to Banana in West Africa before a gruelling three-month journey on foot up the river to Stanley Pool (now Pool Malebo), where it was reconstructed by African workers who had been trained by the mission as blacksmiths, riveters and carpenters.

George Grenfell made a point of encouraging the ambitions of his African workers and promoted the idea that instead of sending across British workers, they should train and employ Africans whose language skills were invaluable.

His British crew members suffered the high casualties that many other Britons experienced and Grenfell got his way. He was able to give proper employment to his African crew, including young John Greenhough/Ti. In a letter to Mr Baynes the Secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society (1885) he says of John, “He is a carpenter, a riveter, having done the lion’s share of rebuilding the Peace. On board he is pilot, mate, quartermaster, and engineer. He was also engaged in making bricks and teaching brick making to the Congo workforce” 5

Life on board The Peace

Once rebuilt, George Grenfell, his family, John/Ti and the rest of the crew would set off for long voyages of discovery inland, lasting between weeks and months at a time.

It was an extremely hazardous life and they found themselves at the mercy of hippos, crocodiles, leopards, elephants, snakes, storms, tornados, unfriendly tribes.

The Peace would set off on its voyages with items to trade for fresh food. Brass was the currency on the Congo; this would take the form of rods or wire. Material (usually red calico) was taken but some more remote tribes didn’t see a value in these things, whereas pretty beads and little looking-glasses were traded and much sought after.

The Peace was shrouded in metal nets and had special shutters which were used to ward off spears and poisonous darts, but the sight of Rose Grenfell on the boat – often with a babe in arms – seemed to pacify those who would have attacked them. This gained her the name of “Peacemaker”. This is because tribes would never take their women to war, so the naturally suspicious tribes that previously saw white men as a danger recognised the boat was arriving in peace 6.

The Grenfells’ mixed-race children were of great fascination and tribespeople would be invited on board to look at the children and allowed to pass the babies around. The children – six in total, with four surviving childhood – lived much of their early life aboard The Peace before they were sent to a boarding school for missionary children in England.

Sarah Greenhough, wife of Rev John Greenhough, would send magazines from England and George Grenfell said everyone that came on board, being unable to read, enjoyed “reading the pictures” 7.

Sometimes Mission school children were taken on voyages. As previous slaves or the children of slaves they had come from distant places but retained some knowledge of their language and were sometimes able to act as interpreters. George Grenfell took great pleasure in reuniting people with their tribes. One young woman was reunited after twenty years!

George Grenfell was awarded the Patron’s Medal by the Geographical Society for his mapping work, but he acknowledged that he had not worked alone in his letters and articles8 (ref 8). His work frequently reached newspapers and mission journals back home.

As more missions became established and spread further east towards the jungles where the rubber trade operated, more stories of atrocities reached the missionaries. Post was controlled by the state and censored, but missionaries managed to send back photos via their own boats and raised awareness of what was happening. This made them very unpopular with King Leopold II and the Belgium people. Later in his life, Grenfell felt that he had been deceived by the authorities and that brutality that had been ascribed to local officials had actually been directed at the most senior level. Britain and the United States campaigned for Leopold II to give up ownership of the Congo. In describing the situation, George Washington Williams in a published open letter to King Leopald II coined the phrase “crimes against humanity” one we know so well today. British and Swedish missionaries were prominent in this campaign and eventually, in 1908, Belgium annexed it from Leopold to form the Belgian Congo.

George wrote to his daughter Caroline as she was about to move to Belgium to train as a teacher. It warns her that as the daughter of a protestant missionary she may need to take her share of the strong public condemnation in Belgium against English missionaries 9

John/Ti’s Success

An update from George Grenfell in 1889 later published in The Missionary Herald gave a detailed update on John Greenhough/Ti, whom Rev. Greenhough had been sponsoring for around fifteen years at this point.

An update from George Grenfell in 1889 later published in The Missionary Herald gave a detailed update on John Greenhough/Ti, whom Rev. Greenhough had been sponsoring for around fifteen years at this point.

John’s reputation had grown and his skills were now in great demand. He had found employment with the neighbouring Dutch Trading Company and had helped build them a new steamer. His salary was five pounds a month. This was a considerable amount of money in Africa, the equivalent of fifteen days of skilled labour in England. With very low living costs in Africa and the fact John still carried out his paid work for the mission in his spare time, he had a very good income.

Grenfell wrote of John “that amid all the temptations of the free and easy trading life he has maintained his position as a consistent Christian.”

“He is by no means the most brilliant of our young men; but for persistence in steady work, or resourcefulness and courage in an emergency, he gives place to none. He may always be depended upon, and has the respect of everyone. He could find employment at any time, either with the state or with any trading house; but I am hoping he will return to us, though I can’t see how he can do so without sacrifice, for we can’t pay him what I know others are ready to give.”

George Grenfell’s letter went on to tell the Rev. Greenhough what he was now doing with the sponsorship money. George intended to fund two boys; Francis and Mongo who were working in the engine room on the Peace.

Mongo had previously been taken in an raid on a village and enslaved. He had been sold to a fellow African for an old coat and a few handkerchiefs. After the death of his master, he had come to the mission and had four years of training.

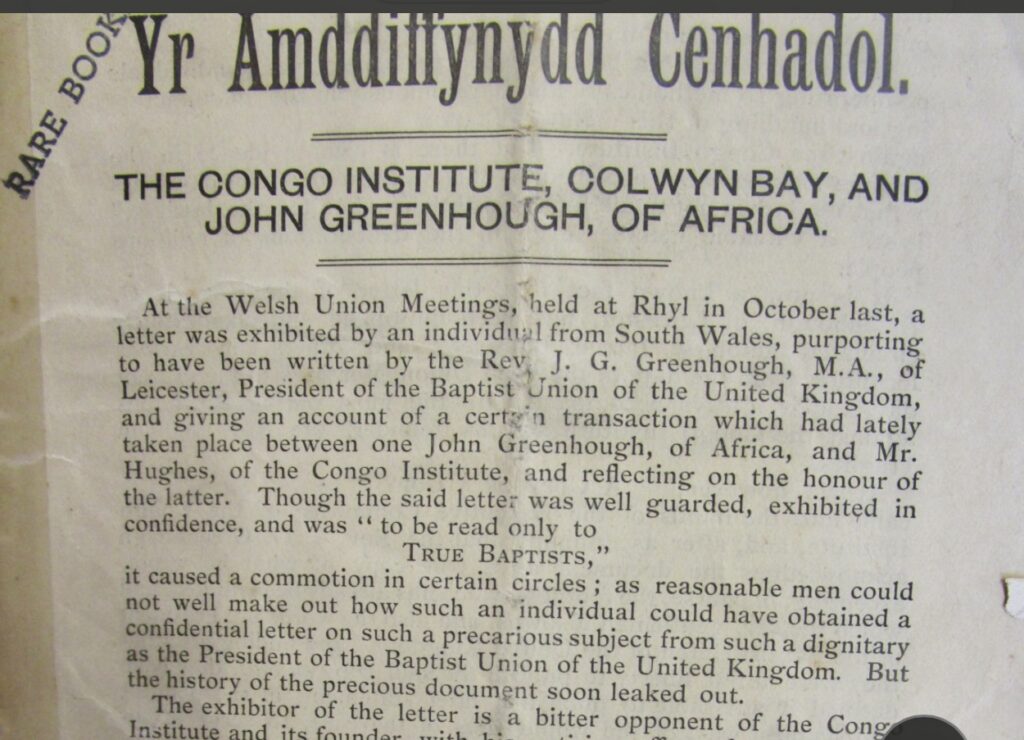

Curious Episode, Leicester 1890s

That is not quite the end of the story. A breakthrough moment at the start of my story when I made the connection between the two John Greenhough’s and George Grenfell involved a financial dispute (ref 1)10.

John/Ti, having benefitted so much from his own development, had wanted to sponsor the education of three African boys. He wanted all three to be educated initially in Africa then the youngest to be brought to the UK and be trained at Edinburgh University as a doctor.

A considerable amount of money was paid to fund this of £247 (valued at £27,000 in 2025) with the promise to send extra money as and when needed.

Unfortunately, the arrangements broke down within the first couple of months, with two of the boys running away from the school. John /Ti decided to abandon the plan and asked for any money not spent to be returned.

The educational institute that had received the money refused and John/Ti travelled to Leicester where his namesake Rev. John Greenhough lived and worked. Rev. Greenhough was by now a prominent minister and the President of the Baptist Union of England and Ireland.

In 1895 Rev. Greenhough helped John/Ti to retrieve the money with threats of litigation. A detailed pamphlet was produced in defence of the educational institute11 . The bitter dispute was finally settled in John/Ti’s favour.

Our Valuable Libraries and Archives

Being able to research this story has only been possible with the help and guidance of authors, librarians and volunteer specialists in our archives in Bradford, Leeds and Oxford. Thank you!

Being guided to and able to view well-maintained and catalogued documents and artefacts is such a privilege. It has highlighted the importance of our libraries and museums to help us learn about and preserve our history and heritage.

References and Further Reading

- Black Students in Imperial Britain, The African Institute, Colwyn Bay, 1889-1911 Robert Burroughs p128-129 ↩︎

- The Life of George Grenfell Congo Missionary and Explorer by George Hawker ↩︎

- Nonconformity and socialism: the case of J.G. Greenhough, 1880-1914

Liam Ryan (2019) www.research-information.bris.ac.uk ↩︎ - Robert Arthington-Philanthropist- The Millionaire Miser

teignmouthcemetery.org.uk ↩︎ - The George Grenfell Collection

Angus Library, Oxford University ↩︎ - Rose Grenfell The Peacemaker

YouTube Windrush70 ↩︎ - The Life of George Grenfell Congo Missionary and Explorer by George Hawker ↩︎

- The George Grenfell Collection

Angus Library, Oxford University ↩︎ - The Life of George Grenfell Congo Missionary and Explorer by George Hawker ↩︎

- Black Students in Imperial Britain, The African Institute, Colwyn Bay, 1889-1911 Robert Burroughs p128-129 ↩︎

- The Congo Institute, Colwyn Bay, and John Greenhough, of Africa 1895

University of Bangor Archives X/EL 359 CON ↩︎

One Response

This is quite the character study! Grenfell sounds like quite the adventurer, though one suspects his resignation might have had a slightly more personal reason than his official biography admits. Its fascinating how Rose, the housekeeper, became the Peacemaker and seems to have been Ti/John Greenhoughs real mother – historys details can be as surprising as a Congolese tribes reaction to a looking-glass! The contrast between Grenfell championing African skills and the broader horrors of the rubber trade he helped expose makes for quite the complex legacy. And John/Ti, sponsored through his education only to see his funding plans collapse – talk about mission drift! A truly captivating glimpse into a turbulent era.quay random