We have a wide-ranging set of collections within Bradford Museums and Galleries, and it’s always interesting to see what people respond to when looking at them. Alice Humphrey is one of our Assistant Curators, who agreed to write a blog for us based on a set of items that caught her eye!

She writes:

I started working at Bradford Museums and Gallery at the end of last year and was delighted to find that they have a collection of Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), since I have a particular interest in Japanese costume. Because of this, I decided to write this post about men’s traditional Japanese costume seen in the ukiyo-e.

Most of the prints in the collection were made at the end of the Edo period in the 1830s-40s although some have later dates in the 1860s. The collection contains a lot of men’s costume depicting both the elite samurai class in the form of historic Japanese warriors and ‘heroes’ and the clothing of the majority of the population – peasants, artisans and merchants in figures depicted on scenic prints and as servants in the background of portrait prints.

The clothing worn by commoners depicted on the print above shows the popularity of indigo as a dye, at the time this would have been from the native plant Japanese indigo not the internationally commercially important indigo plant. Indigo was popular with the commoners because it allowed fabric from old garments to be cut up removing worn sections and then patchworked into new garments and dyed with indigo which gave an intense colour and covered up existing patterns on the fabric. The print shows many of the types of patterning commonly found in Japan at the time: stripes, lattices and, small geometric patterning covering the whole garment. The large designs of the three rotating commas (hidari mitsudomoe) known as mon are similar to family crests and, in this instance, identify the porters on the bridge as being affiliated to the Arima clan. Characters printed or woven on costume typically had auspicious meanings for luck, wealth or prosperity.

The men shown in the landscape prints are wearing padded hanten – short jackets and monpe – trousers of a style which contrasts with those worn by the warrior class in having narrower legs reaching only to the calves, more practical for manual work; the shins are covered with a type of gaiter (kyahan), flat pieces of cloth fastened with ties. One of the men in the centre of the print above is also wearing a sodenashi – a sleeveless jacket which would provide some extra padding against the load he is carrying. Clothing for farmers, who made up the majority of the population, would typically be made of hemp fibre or cotton, woven and made up within the home providing for the needs of the family and sometimes also an income. Typically, the clothing was decorated using woven or stencil resist dyed patterning or a style of embroidery called sashiko. The stencil dyeing, technique used paper stencils through which a rice-glue was applied preventing those areas of the fabric taking up colour when it was dipped in the dye vat. After dyeing the resist glue would be washed out of the cloth. Sashiko embroidery takes the form of small tessellating geometric patterns covering the whole garment as well as decoration, the technique aided with holding padding and small patchworked fabric pieces securely in position.

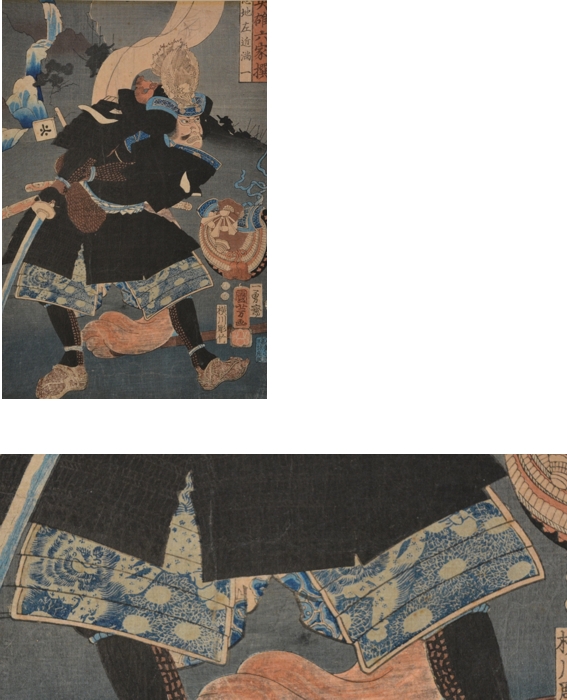

The samurai depicted on the ukiyo-e wear clothing indicative of their status. This typically consisted of: an under kimono, which would not be seen and was worn to keep the kimono clean, the kimono which was often highly decorated and tied at the waist with a sash obi; over this would be worn andon hakama – undivided, stiff-pleated trousers. The print above shows a particularly beautifully decorated example of hakama with a finely detailed design of lions and peonies; this design pairing has a Chinese origin. In Japan, the peony and lion combination was associated with the concepts of wealth and power.

Traditional Japanese clothing reflected the seasons in patterning; the print above, shows an actor playing a samurai. The character is wearing a haori (a jacket similar to a hanten, without the padding over the kimono) with roundels containing plum, pine and bamboo. This combination is known as the Three Friends of Winter; pine stay green through winter, bamboo show resilience to the winter winds, and plum is one the earliest flowering trees in Japan and may flower when snow is still on the ground. The samurai in the print above is also wearing a rice straw raincoat and hat. Differing styles of broad straw hats were worn by all social groups when working outdoors or travelling, the hat in this case is a takuhatsugasa which covers the top part of the face. The samurai in the snow, at the end of this post is wearing the amigasa, a style of hat particularly associated with samurai. Both of these contrast with the, wider and shallower, sandogasa worn by the general population, shown in the detail from a print below.

It can be seen from the print below, that blue and white patterning was popular across social divisions but samurai also had access to more colourful fabrics – the floral sleeves visible in this print may have been silk brocade weave, painted designs or silk embroidery using long and very densely packed stitches to produce blocks of colour; these were time consuming so expensive techniques only available to the wealthy.

As a resource for learning about costume, ukiyo-e prints provide a particularly valuable opportunity to see the clothing worn by peasantry, artisans and merchants whose clothes were often worn to destruction so fewer examples are preserved and to see how the clothes were worn and combined as well as the context in which different clothing was worn.

6 Responses

Such a pity missed this exhibition, can you tell me if it will be on again at Cliffe Castle in the near future.

This particular exhibition was in 2016, and we have an an exhibition a bit more recently that looked at some of these items.

They aren’t currently on display, but one of our volunteers is busy working on researching more about these items – which we can hopefully share in future posts!

Can you tell me if Dale Keaton is still the curator at Cliffe Castle? Has he worked there since the early 90’s when the castle underwent extensive renovation to the porch and hall decoration.

kind regards

Christine Westbrook

(formerly from ‘Designs On You’)

Dale is still working for museums, yes!

Strangely enough, we’d been talking about the dates the decoration in the porch and corridor happened the week you made contact. What a lovely coincidence!

Thank you foryour prompt reply Heather. Hopefully we will once again have an exhibition of this facinating culture.

Regards

Christine

Thank you foryour prompt reply Heather. Hopefully we will once again have an exhibition of this facinating culture.

Regards

Christine