UK Disability History Month is an annual event, run in November every year since 2010. If you’d like to learn more about the nation-wide event, their website can be found here

The theme for this year is War and impairment: The Social Consequence of Disablement, something that our Curator, Liz McIvor ,addresses as part of the Bradford’s War 1914-18 Exhibition, on display at Bradford Industrial Museum until the 19th November.

Liz writes:

This year, audiences have been exposed to stories of servicemen of World War One returning home with disabilities and what it meant to be disabled in the 20th century. It is interesting to compare that kind of experience with those from the more distant past and some of the attitudes of our ancestors to disability.

In Medieval England disabled people were expected to be part of the community, to work and contribute to the family income as much as possible, and where this was not possible, to be cared for by relatives. The strong cultural belief in the ‘wheel of fortune’ meant that people generally viewed disability as a natural part of life (although also as a physical sign of judgement against worldly sins), and something that could and did affect anyone, regardless of birth, through war, disease, and accidents.

Rural populations (such as Bradford district) were small, so everyone in the town knew one another. This was a fervently religious and insular culture, which meant it was difficult to ignore those who needed assistance. Generally people would be defined by which family or trade they belonged to, rather than their disability.

People in records appear as ‘John the Carpenter..Who is crippled’ rather than ‘John the Cripple’. Only occasionally do sources reveal what we would term a disability; Born in 1280 Henry Plantagent 3rd Earl of Lancaster and Leicester (under which Bradford was controlled) was a senior noble at the highest level of 14th century politics, despite being blind.

For some, disability was the source of their income. Noble houses employed ‘natural fools’ and esteemed them greatly as trustworthy and loyal. These would usually be people who had learning difficulties and could earn enormous sums of money as privileged members of a household. People with achondroplasia (Dwarves) were particularly prized as companions and entertainers for centuries.

The beginning of the 17th century saw developments of legislation towards ‘provision’ for those who could not support themselves through the ‘Act for the relief of the poor’ in the reign of Elizabeth I.

This was the result of an explosion of population and growth of towns. The country was growing richer and more people began to move about freely and form larger communities. These did not have the same bonds of family, friendship and church, and in a more anonymous society, more disabled people found themselves faced with competition, poor and forced to resort to begging.

“By taxation, every inhabitant and occupier of house or lands should lay on sum of money and a convenient stock of flax, hemp, wooll, thread, iron and other wares and stuff to set the poor on work”

“That the necessary relief of the lame, impotent, old and blind and other such among them, being poor and not able to work.”

Anno 43 Elizabeth Cap II (1601)

The experience of being disabled very much depended on a person’s social status, so as workhouses and asylums were opened to take patients, wealthy people might still be cared for at home.

Bolling Hall was inherited by Francis Lindley who was described as a ‘Lunatic’ (meaning learning difficulties) in the 1700’s and despite this was legal heir to the property which passed to his cousins, and not the sisters who cared for him.

As urbanisation continued, the provision for those ‘on the parish’ did not keep pace, so as Bradford’s population skyrocketed in the early 1800s with the industrial revolution, there was limited space in the workhouse (now St Luke’s Hospital) and conditions were purposely kept poor. With the poorest families forced to work long hours with poor housing, food and no medical care, the workhouse was often the only option for a sick or injured relative. As a result, the disabled population grew, and were more visible on the streets in Victorian England.

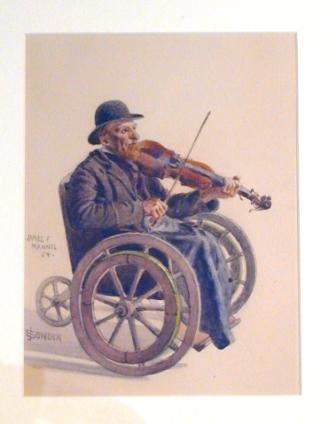

The Bradford artist John Sowden was interested in the ‘street people’ of the town and particularly those who made a living despite adversity. Although he paid men and women to sit for him, there is little evidence that he tried to help them in other ways. He saw the people he painted as ‘picturesque’ and noble in adversity and painted them for his own entertainment.

In 1888 he painted James Mannis, paralysed from the waist down after a childhood illness, which was most likely to have been the Polio virus, which is spread easily in urban areas with poor sanitation.

Sowden’s wife Anne was affected by ‘melancholy’ or depressive mental illness, possibly brought on by post-partum psychosis after the birth of their son, and lived as a recluse at their home in Manningham.

Bradford’s disabled population today is as diverse as the rest of the city, and there are a number of services and initiatives to provide support, working towards a fairer and more representative society.

The way we approach disabled audiences is based on the people who inhabited our past and what we can learn from them.

Bradford Museums and Galleries are interested in acquiring objects and stories which represent disabled people.

Contact the Social History Curatorial Team via the contact details on http://www.bradfordmuseums.org/contactus/index.php. You can also make initial contact via our social media accounts and we can pop you in contact with the Social History team.