Bradford Christmas Waits

As the festive period is in full swing, one of our Assistant Curators of Collections, Dr Lauren Padgett, has been looking into a lesser-known bygone Christmas tradition in nineteenth-century Bradford of the Christmas Waits.

Christmas is full of traditions. There was a Christmas tradition in nineteenth-century Bradford which hasn’t been written about much and subsequently forgotten over time: the Christmas Waits. We have, however, been left with two obscure but detailed nineteenth-century accounts which I have used to piece this Bradford Christmas custom together. One was written by Bradford historian William Scruton1 and the other by local author, journalist and social commentator James Burnley2.

At the time of writing in 1888, Scruton acknowledged that ‘several years have now passed away since the old Christmas Waits were last heard in the streets’ and prophesised that ‘when a few more years have rolled away the fact that they ever existed at all will be spoken of as a thing only of the “olden time”’. He explained how in 1829, Mr Ellis Cunliffe Lister (the father of Mr Samuel Cunliffe Lister, Bradford textile baron) and Mr Matthew Thompson were magistrates in Bradford and gave Samuel Smith (known locally as ‘Blind Sam’) permission to form a company of Waits for Bradford.

Town Waits were originally watchmen who would use a musical instrument to signify that they were on duty and to mark the hour. Eventually this role developed and Waits became more skilled with their instruments and would work as a group or company. Waits were employed by the town to conduct this duty and would be called upon to perform at ceremonial occasions. The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 meant that Waits were abolished but some companies continued as Christmas Waits, singing and playing Christmas carols in exchange for money and gifts over the Christmas period.

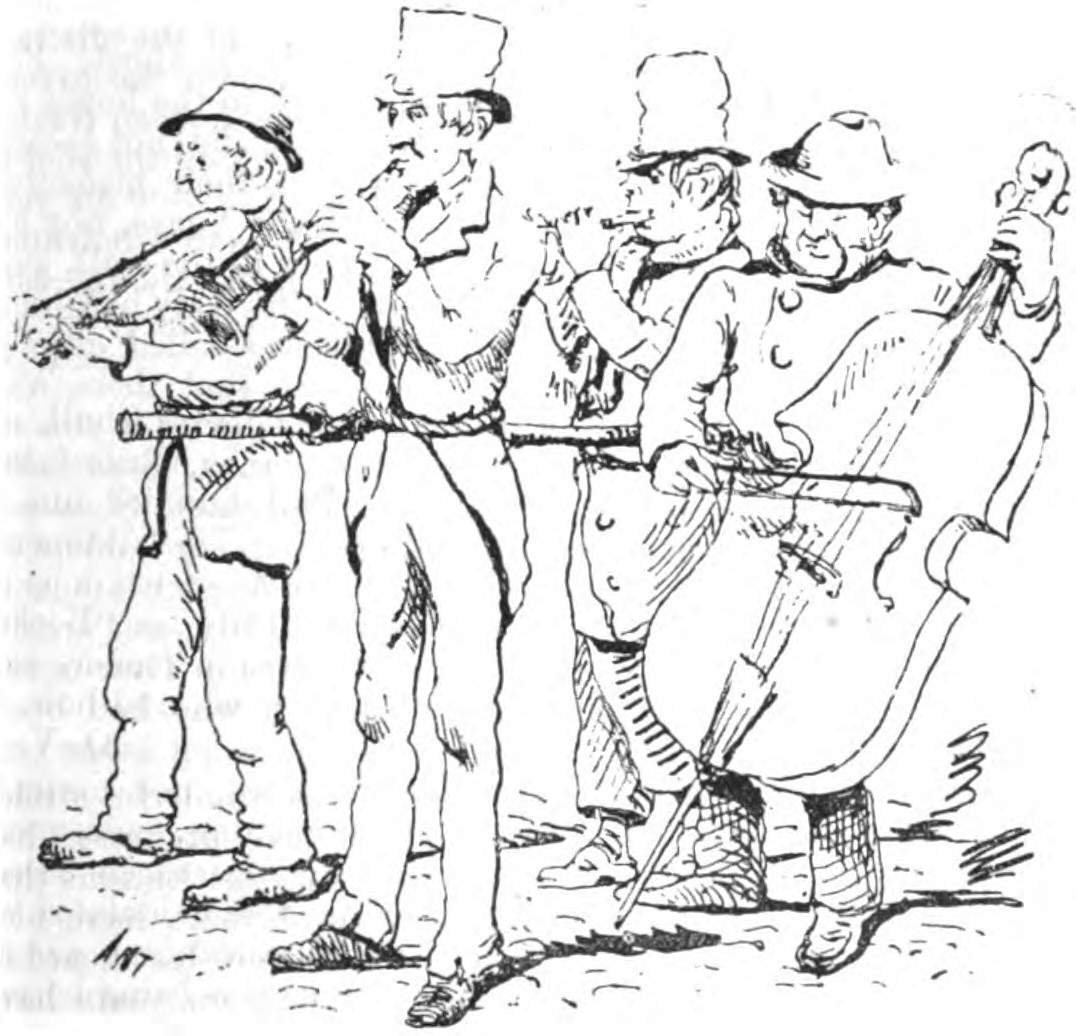

With permission approved in 1829, Sam Smith then found other blind musicians to join his company: James Fletcher (also known as both Jem and Jim), Billy Blazeby and Jack Dodge. Carrying their musical instruments and all tied to a long pole so they would remain together, in the evenings and into the night, they would be led around Bradford by a blind or sighted guide who knew the way, ‘making music that could hardly be called sweet’.

Drama ensued in 1862 when a rival Waits company, ‘The New Borough waits’, formed causing ‘jealousies, bickerings and retaliations’ according to Scruton. Mr Abraham Holroyd (another local historian) declared it ‘very foolish, if the parties concerned had only considered that Bradford was then five times as large as it was thirty years previously’. According to Holroyd, Bradford could accommodate both companies ‘if they had only agreed to divide the Borough and the yearly gifts between them, there was plenty of room for both bands, and two more if competition must come’. Scruton was unsure about whether Bradford eventually came to terms with having two Waits companies, but he does point out that ‘both the old set and the new, have ceased to exist, and will in course of time pass into the limbo of “forgotten things”’.

Bradford’s (original) Christmas Waits make an animated appearance in James Burnley’s 1875 book West Riding Sketches. Burnley recounts ‘A Night with the Waits’ when, like an intrepid detective or astute social commentator, he tracked them down in Bradford one cold night and interviewed them. He described them in almost romanticised and mythicised terms calling them ‘the profoundest mysteries of creation. Like owls and bats, they belong to the night, and like then, they are more frequently heard of than seen’. They are grounded slightly with the following sentence which says he had ‘a friend who once conversed for ten minutes with the Clarionet [player] over a pint of Yorkshire stingo’. Burnley’s account, while flamboyant and self-indulgent, is fascinating to me as it places them specific Bradford streets and gives an insight into who they were, what they did and the response they received from Bradfordians.

Burnley himself had an ‘appreciation of their talents’ but this wasn’t universal by all Bradfordians as he went on to say ‘I have little sympathy with those newspaper correspondents who whine about them annually in print’, but ‘despite the petty objections advanced by their detractors, the Christmas Waits are not generally despised’. Burnley’s encounter with them was prompted by them waking him up ‘a few weeks prior to Christmas’. ‘As their music died off in the distance . . . [he] conceived the idea of making their acquaintance’. After making some inquiries, eventually he was told that they were likely to be on Manchester Road so, with a companion called Barnacles, he set out to find them. They ended up pursuing ‘a male figure’ ‘carrying an instrument encased in a bag’ with ‘greyhound fleetness and stealth’ but, alas, it was a case of mistaken identity.

After unsuccessful inquiries on the following nights, they eventually found the Waits around the bottom of Horton Lane in the early hours one morning. Burnley described them:

‘The oldest of the trio was a tall, gaunt man, with a face of silent melancholy. This was the Clarionet. The other two were players on stringed instruments – the second violin and the violoncello. He of the second fiddle wore a picturesque “billycock” and evinced a gaiety of demeanour which was lacking in the others’.

They were then joined by another companion. Burnley and Barnacles stayed with them while they tuned their instruments and then followed them as they made their way up Great Horton Road, listening to them playing songs under bedroom windows and asking them questions during intervals. The ‘Clarionet’ [sic], as he is referred to, said he had been a Wait for 29 years while ‘one of the Violins’ explained (in local dialect) that:

‘We begin five weeks afore Kirsmas an’ give over at Kirsmas Day. We meet ivvery neet – ah mean mornin’ – between twelve an’ one, an’ tak up whear we left off t’mornin’ afore’.

When asked about the rival group of Waits, the Clarionet replied

‘we’ve no connection wi’ ‘em, we’re t’owd orginal set . . . it affects is a girt deal . . . ‘cos we sometimes find they’ve been at places afore us. Some fowk divide what they hev to give between us, an’ other fowk ‘ll nobbut give to one’.

As it got colder and later, Burnley and Barnacles said goodbye to the ‘wandering minstrels’ and the account ends there.

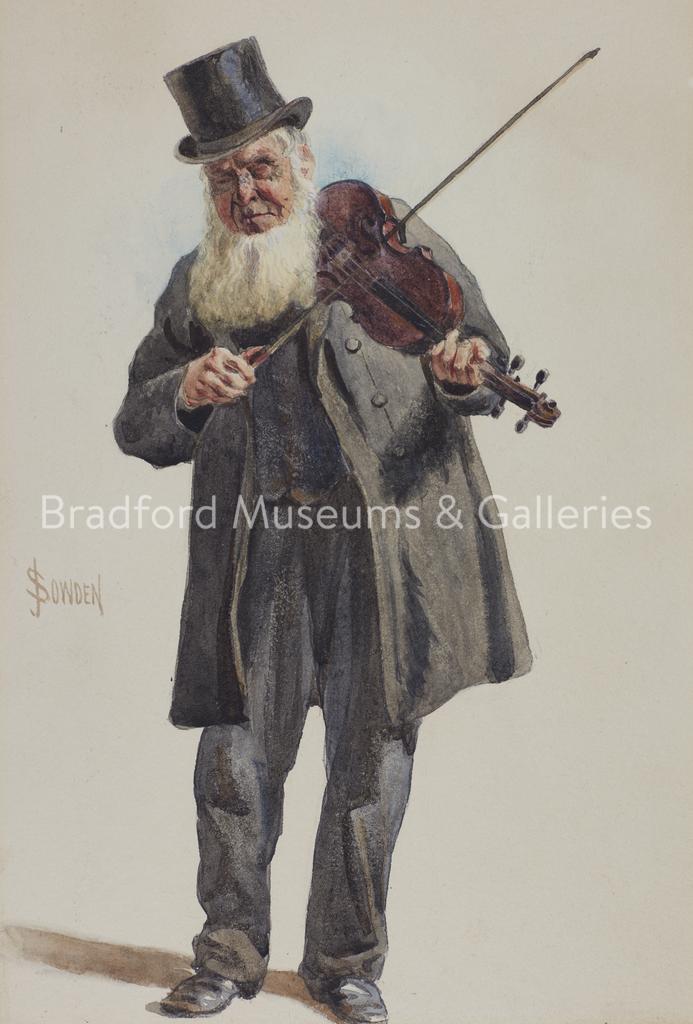

What became of the Bradford Waits when they disbanded? In our collection, we have some portraits of ‘street characters’ painted by John Sowden at the end of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century. James (or Jem or Jim) Fletcher, known locally as ‘Blind Jim’, was one of them. James was 83 years old when Sowden painted him with his stringed instrument. Sowden’s notes in his diary indicated that James was still known for his past life as one of the Christmas Waits, and stated that after they split up, James continued as a solo musician in pubs and on the streets. James had married a blind woman and was married to her for 43 years until she died, and he remarried in his seventies.

I turned to census records for more information about him and the 1871 census return shows a James and Martha Fletcher living at 83 King Street, Bradford. James is a 65 years old ‘musician’ and Martha is 77 years old. It is noted that James was ‘blind from 9 months old’ and Martha ‘blind from smallpox from 7 years old’. The 1881 census return shows James still at King Street, aged 75 and listed as a ‘violinist’ and ‘blind’, but he is now married to Betty, aged 64.

This December, think about how 150 years ago in Bradford, you might have been disturbed in the small hours by two competing tropes of musicians playing Christmas carols under your bedroom window.

18 November – 18 December 2020 is Disability History Month

1 William Scruton, Yorkshire Notes and Queries, vol. 1, 1888, pp. 234-236.

2 James Burnley, West Riding Sketches, 1875, pp. 334 – 351.

3 William Scruton, Pen and Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford, 1889.

4 Responses

Excellent, really entertaining. A modern-day Waits group would generate interest in the local news bringing festive joy.

[I think in the last paragraph you mean troupes, not ‘tropes’.]

Thank you. Very interesting. I think we should start up the tradition again for insomniacs, perhaps, who can sing well.🤣

But maybe sing from 9:00 to 11:00? Hopefully they will get worn out then actually sleep!

A bit late for Christmas 2020, now 2026, but just read about the ‘WAITS”.

My family history research took me to 93 Silsbridge Lane in the West Ward of Bradford. This was the house of Samuel Smith, a blind musician.

My first thought was, this is unusual I wonder if there is anything on the internet about the man. Then I found your wonderful piece of research. A copy of that will now go into my Family History research along with the other 16,667 other links to my family.

Thank you very much.

We love it when people contact us to say they’ve found the information we’re sharing useful – thanks for taking the time to let us know!