This blog post by Liz McIvor, our Curator for Social History & Technology takes a look at the broadsheets and broadsides popular in the past – the ‘Social Media’ of years past

Items described as ‘paper ephemera’ in Museums and Galleries can mean anything from bus tickets to receipts for dry-cleaning. Although most paper sources, and certainly documents end up being cared for by archives, some of these more domestic pieces of paper from the lives of ordinary people are part of our collections because of what they tell us about everyday life, food, fashion, beliefs and events of the day.

Some of the most interesting are the broadsheet or broadsides; not the modern newspaper for the intellectual, but small, cheaply printed pieces of paper sold on the streets and designed to be consumed by the masses.

They appeared from the 1600’s until the 20th century and the purpose was less that they should be read, than listened to. Popular sheets concentrated on the topics that most interested or entertained people, usually crime and scandal, political developments and public grievances. They often make the subject into an amusing poem or song, which, once read out and repeated helped people to remember it and spread the message.

Official newspapers and journalists had to be very careful about the stories they wrote because they could be held to account for inaccuracy and libel. This was not true of broadside printers, who had no premises or licences and who’s names do not generally appear on their work except as an ‘alias’. It meant that the people who wrote and distributed them could say what they wished, and by doing so, influence the opinion of people who would not read the papers.

An early ballad printed in the 1660’s in the collection of the British Library (Ref Roxburgh 4.35) called the ‘Clothier’s Delight, printed using woodcuts, complains of the ‘Rich man’s joy, and the poor man’s sorrow, caused by merchants in textile towns paying cottage cloth makers poor wages, and selling their goods for high prices.

“Then hey for the cloathing trade, on it goes brave,

We scorn for to toyl and moyl, nor yet to slave;

Our work-men do work hard, but we live at ease,

We go when we will, and come when we please.

We hoard up our bags of silver and gold,

But conscience and charity with us is cold.

By poor people’s labour we fill up our purse,

Although we do get it with many a curse.”

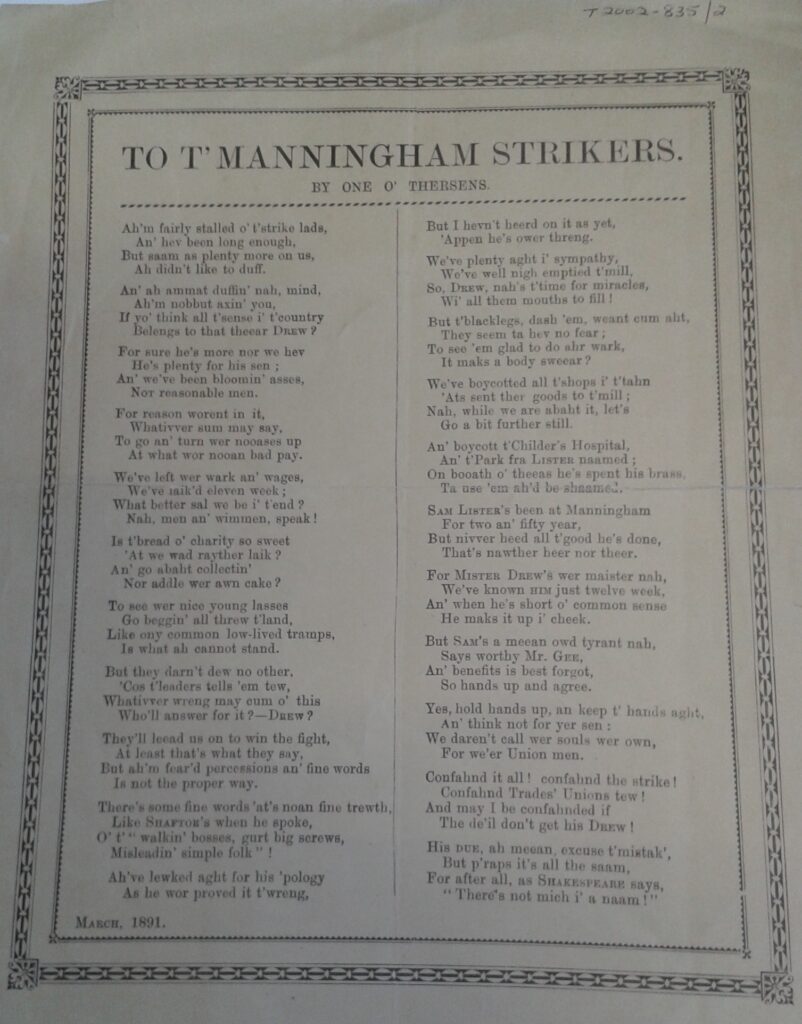

The tradition carried on from the pre-industrial society to the turn of the 20th century. One such example is the relatively late ‘To T’ Manningham Mills Strikers’ pictured here, in the Technology Collections of Bradford Museums and Galleries.

It is dated March 1891 in the middle of the famous Manningham Mills Strike for pay which, although ultimately unsuccessful, was to have a massive affect on the numbers of workers joining trade unions, and the support of the Independent Labour Party and the Bradford Labour Union.

There had been a number of previous disputes over hours and pay, but when it was announced to the plush velvet weavers that their pay was to be cut from Christmas Eve 1890, a committee was formed to strike. William Drew was representative to a thousand workers under the Weaver’s Association and it is he who is lambasted in the poem as an interfering and thoughtless outsider.

One of Millowner Samuel Lister Lord Masham’s letters reports property damage to the mill and he complains

“The strikers are still allowed to beg from house to house. I believe it is contrary to the law, but the Mayor does not seem to have the courage to enforce and stop it. To give you an idea of how bitter Manningham is against us, some of the people that had their windows broken, the Manningham plumbers refused to put them in, and they were obliged to go to Bradford.” REF880/2

The broadside is clearly aimed at changing opinion in the area in an ‘appealing voice’ written by ‘One O’ Thersens’ to put down the strike leaders and praise Samuel Lister.

“We’ve boycotted all t’shops in t’than

‘Ats sent ther goods to t’mill;

Nah, while we are abaht it. Let’s

Go a bit further still.

An’ boycott t’Childer’s Hospital,

An t’park fra Lister named;

On booth o’ these he’s spent his brass.

To use ‘em ah’d be shaamed.

Sam Lister’s been at Manningham

For two and fifty year,

But nivver heed all t’good he’s done

That’s nawther heer not theer.”

Written with a broad Bradford accent, this piece is somewhat patronising and clearly written by an educated man, because all the correct words are capitalised and the writer often forgets how he has spelt an accented word such as there, which he spells theear, ther, theer, and there as well as references to Shakespeare in the closing verse. Using ballads and broadsheets as history is difficult, because they are often biased, but they are useful for confirming attitudes as well as evidence that people were well informed about a complex issue.

The strikers failed in their mission because Lister and Co who ran Manningham Mills used their healthy profits to buy in new labour and re-direct operations. The opposition was heavy handed, in that volunteer troops were stationed around the mill, and other workplaces to prevent protesters from campaigning.

A strike fund and soup kitchen was set up by local people and charities, and contributions to the fund came in from all over the country, – from textile workers as well as those in other industries; but the union men were unable to control the numbers ‘coming out’ as not all of the workers were in unions. With too much pressure on the strike relief fund over one of the coldest winters on public record, many men and women could no longer survive without pay. After four months of misery, the strike was declared broken.

The formation of the Independent Labour Party at the same time led to a greater representation, especially in the years after the First World War, of working people in the parliamentary system and growing influence of the trades unions in the 20th century.

The cultural use of broadsides and cheap ballads fell in the 20th century because of a rapid rise in literacy levels and access to other forms of information and opinion such as magazines, daily papers including tabloids, aimed at the working classes, and the development of public broadcasting in Radio and Television.

Recent research by Reuters Department for Journalism and the poll YouGov has suggested that 75% of UK residents access news every day and that over 80% of current affairs consumption and commentary is online via news apps and social media outlets.